A picture of working students in OECD countries

[ad_1]

By Glenda Quintini.

The combination of work and study has been hailed as crucial to ensure that youth develop the skills required on the labour market so that transitions from school to work are shorter and smoother. As a result, in the current context of record high unemployment rates, many governments have set out to encourage learning on the job, particularly when it comes as part of certified programmes such as vocational education and training pathways (VET) or apprenticeships. Despite this central role in current policy thinking, comparative statistics on work and study are hard to come by and information is patchy at best when it comes to the context in which most students work – crucially, whether there is a (formal or informal) link between their schooling and their job.

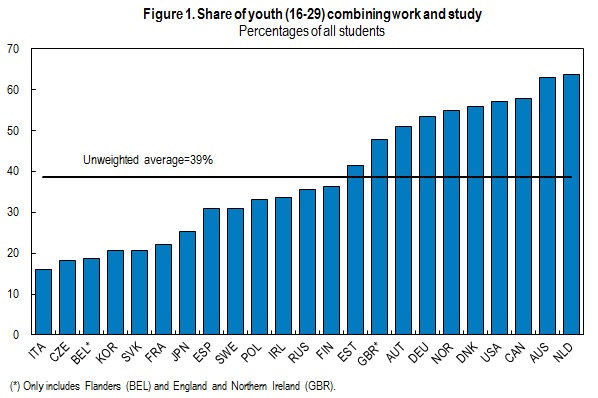

A new paper by Glenda Quintini (2015) fills this important gap and draws a comprehensive picture of work and study in 23 countries/regions participating in the 2012 Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC). The study finds that 39% of students work on average across these countries, an incidence that ranges from about 15% in Italy to over 60% in the Netherlands (Figure 1). While apprenticeship schemes and VET programmes account for up to 50% of all work-and-study in some countries, the vast majority of students work outside these formalised programmes, most of them in jobs that are not related to their field of study.

Two factors are often put forward in discussion of whether combining work and study improves labour market outcomes later in life: a) the link between the work done and studies being pursued; and b) the number of hours worked. The study by Quintini sheds light on both these issues. It finds that a large share of student jobs are unrelated to the students’ field of study – ranging from 65% in the US and 35% in Austria. The number of hours worked is also an important factor in students’ jobs because of the need to leave enough time to attend courses and prepare exams. The study finds that the extent to which students work part-time or full-time is less related to the incidence of part-time in the country than to the nature of work and study. For instance, on average 73% of apprentices report working full-time compared with just 49% of VET students and 40% of students working under other arrangements.

Source: OECD calculations based on Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) (2012).

More flexible labour markets where hiring and firing are relatively easy and part-time is widespread are found to be more conducive of students’ work while a negative correlation is found with the ratio of the minimum-to-median wage in the country which may make it too costly for employers to hire inexperienced students. Another interesting finding is that, despite strong gender stereotyping in some VET and apprenticeship programmes, gender is not found to influence the likelihood of work and study, once other factors are controlled for.

Finally, the study finds a negative correlation between the share of students who work and study and youth unemployment (Figure 2). This needs to be taken with care as it is not clear what causes what.

Source: OECD calculations based on Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) (2012).

Photo Credit: ©Shutterstock

[ad_2]