Decision Change: The First Step to System Change

1. Introduction

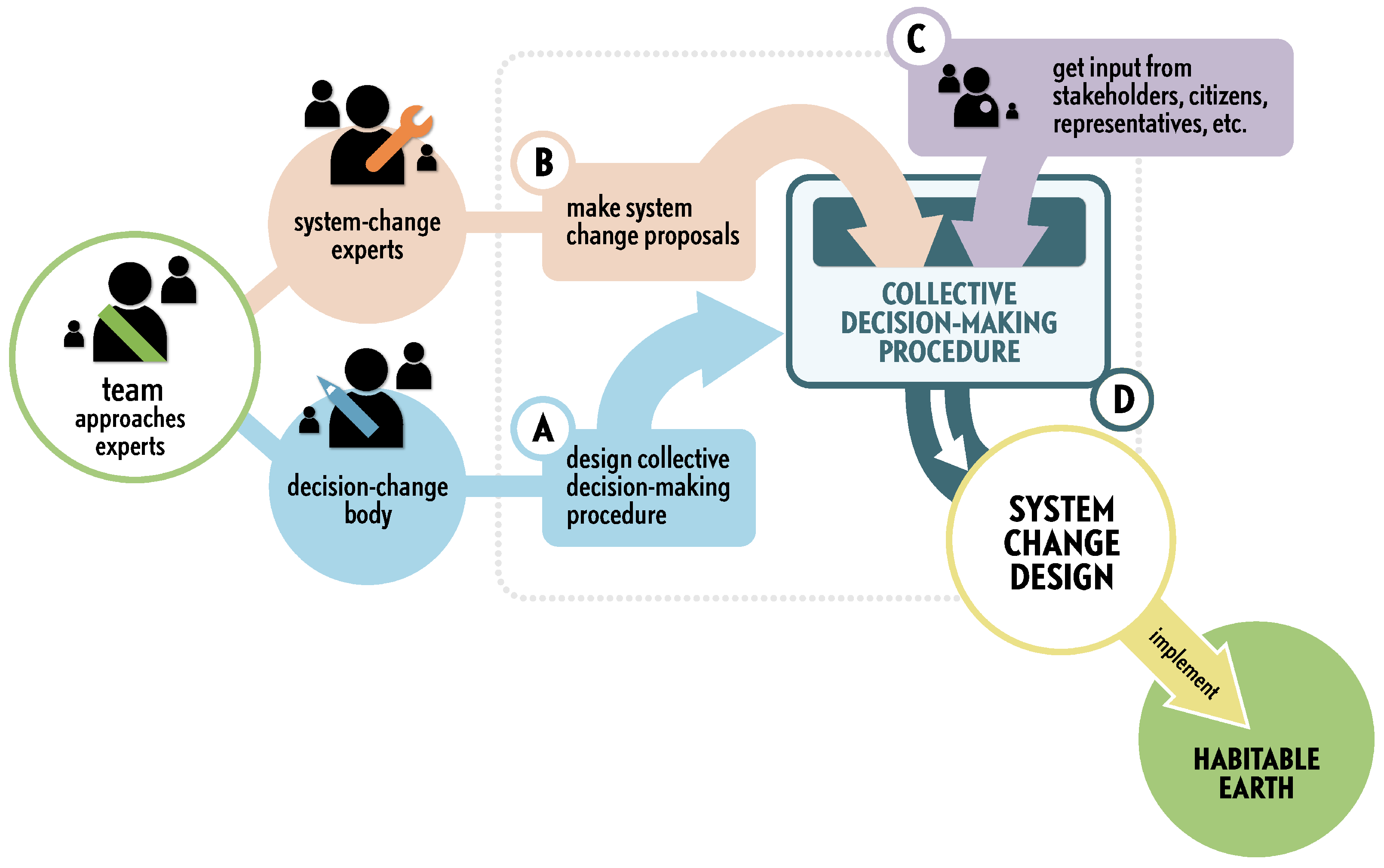

Rather than closely examining such proposals, we identify an underlying ‘meta-coordination’ problem: there is no structure that allows us to effectively decide on alternatives to the COPs and similar conferences. The question is how and by whom an alternative decision-making procedure should be designed and what the scope of its use should be. In this essay we suggest that independent experts in collective decision-making, monitored by auxiliary bodies, design a new procedure to decide on the required system change; this design we call decision change. Additionally, we propose that a global team convenes the expert meetings, assembles the auxiliary bodies, collects system-change proposals, and initiates the decision-making on system change. These proposals constitute an actionable research programme that would have to be facilitated by an independent organisation.

2. Problems

In this section, we work back from the COPs on biophysical crises to the underlying problem—the lack of a structure for effectively selecting alternatives to the COPs, in particular for deciding on system change.

2.1. COPs and Crises

2.2. Decision-Making by the United Nations

2.3. Systems Approach

2.4. Global Governance

2.5. Alternative Global Governance

3. Meta-Decision Structures

Various organisations and other structures exist that help to select a procedure for deciding on specific global affairs, such as climate change, but not explicitly on system change. These meta-decision structures are briefly reviewed here to demonstrate the novelty and relevance of our proposal for allowing decision-making experts and others to form this structure.

4. Decision-Making Experts

Table 1.

Fields of decision-making theory.

Table 1.

Fields of decision-making theory.

| Concise Descriptions of Some Important Fields of Decision-Making Theory |

|---|

| Social-choice theory is concerned with the aggregation of judgements or preferences, such as through various voting procedures [89,90,91]. To illustrate, an impossibility theorem states, loosely speaking, that no procedure for collective decision-making can recognise ‘objective basic needs or universal criteria’ [92]. |

| Public-choice theory considers decision-makers to be self-interested agents, as in an economy [93]. |

| Multiple-attribute group decision-making [94]. |

| Global governance [95], defined as repeated decision-making. |

| Decision-making based on wisdom, knowledge and reason. For governance, this is known as noöcracy [96], epistocracy [97,98], or epistemic democracy [99], and more generally, as collective reasoning [100]. |

| Negotiation [101] and the theory of mathematical games, including mechanism design [102]. |

| Deliberation, such as in citizens’ assemblies, comprising randomly selected citizens who inform themselves and decide collectively, often subject to group dynamics [103,104]. |

| Representation and delegation [105,106]. |

| Argumentation theory, that is, logic, rhetoric, and public discourse [107,108]. |

| Analytical methods, such as cost-benefit analysis [109]. |

| Individual decision-making and its fallacies [110]. |

5. Design of a Decision-Making Procedure

-

Design: Independent experts in collective decision-making design a one-time decision-making procedure (medium-sized circle), while being monitored by auxiliary bodies (suggestions in Appendix A.2). The decision-making experts and auxiliary bodies are collectively called the decision-change body (lower box). Designing a decision-making procedure basically is a process of deciding how to decide, which follows a meta-decision method (larger circle and the upward arrow protruding from the lower box). This method is also to be selected by the experts, who already possess the required expertise and theoretical understanding, such as social-choice theory (lower dashed arrow). Suggestions for the meta-decision method are in Appendix A.1.

-

Collection of system-change proposals: If unprepared, the decision-making body would possess only a limited array of system-change proposals and be faced with the daunting task of inventing additional proposals from the start. Therefore, proposals would have to be collected in advance to provide a head start, after which more proposals can be added (upper dashed arrow). Although this step should actually be designed by the decision-making experts, it has been inserted to show the experts that proposals will be available to decide upon.

-

Decision: The decision-making body (upper box) employs the decision-making procedure designed by the decision-change body. Using system-change proposals (upper dashed arrow), the decision-making body decides on issues such as an economy based on wellbeing indicators (‘other system change’) as well as governance (that is, repeated decision-making), which may differ from the decision-making procedure used for its selection.

The following formal reasoning makes plausible that the decision-making procedure for system change is likely to process a variety of proposals and arguments adequately. First, the procedure (medium-sized circle) is probably well-founded because A. it is based on decision-making theory and expertise (lower dashed arrow); B. this information is processed well, since the design process (lower upward arrow) is safeguarded by auxiliary bodies. To guarantee independency of the decision-change body, these auxiliary bodies should not, for example, admit representatives of UN member states to the process of designing a decision-making procedure. Second, the resulting decision on system change is likely to be a trade-off between effectiveness and fairness (to deal with shortages) because A. many system-change proposals are submitted and arguments are advanced (upper dashed arrow); B. as just shown, the decision-making procedure probably is well-founded, so it may adequately process these considerations. For example, it is unlikely that the conclusion of the decision-making experts is to have any of the UN member states play a decisive role (as with the COPs) in the decision on system change.

6. Coordination

- A

-

Compose the decision-change body (at the left of the rectangle); that is, convene independent experts in collective decision-making and assemble the auxiliary bodies. For details about independency, see Appendix A.2, second point. The decision-change body designs a procedure (box with a slit) to collectively decide on system change.

- B

-

Collect initial system-change proposals from experts in relevant subject areas, not only as a head start, but also to convince decision-making experts to participate by making it plausible that their decision-making procedure will be implemented.

- C

-

Collect proposals and other input from the public. (At least, this is our suggestion: Appendix A.3, paragraph about content.) Box C represents the inputs from both the decision-making body and other parties.

- D

-

The decision-making body should combine the proposals and other input according to the selected decision-making procedure. The team only needs to initiate this final stage, that is, ensure that it is organised.

The result of this programme would be a system-change design. In the most optimistic scenario, its implementation keeps the earth habitable.

Figure 3.

Coordination of the programme. The programme comprises four main steps (A, B, C and D) and is coordinated by a team. For copyright, see acknowledgements.

Figure 3.

Coordination of the programme. The programme comprises four main steps (A, B, C and D) and is coordinated by a team. For copyright, see acknowledgements.

7. Discussion

To summarise, as global crises intensify, the need for a procedure to decide on system change becomes increasingly urgent. Independent experts in collective decision-making, including design theory and problem analysis, should design this decision-making procedure; various auxiliary bodies must safeguard the design process; proposals for system change should be collected; and with the aid of the procedure, a decision is to be taken on system change. These steps are collectively referred to as the programme for decision and system change. Notably, the experts do not design actual changes but a procedure by which others decide on system change.

7.1. Potential Advantages of the Programme

The decision-making procedure would probably suppress conflicts of interest. During design of the decision-making procedure, there might already be conflicts of interest because the organisation that backs the team cannot be entirely independent (politically, ideologically, or commercially), even if it is financed by other organisations. Nevertheless, the decision-change body would be able to design a procedure to decide on system change that is as resistant to conflicts of interest as possible.

7.2. Potential Limitations of the Programme

Further, despite the presence of auxiliary bodies, decision-making experts may be suspected of promoting or ignoring certain interest groups, or of approaching decision-making too technically.

Additionally, the programme might be misinterpreted as a decision on system change instead of a decision on decision-making, or decision-making experts might be confused with expert decision makers, that is, with experts in a subject matter who make decisions (‘technocrats’). In particular, experts in governance could be tempted to propose specific forms of global governance rather than indicate how to decide on this topic and other system change.

Finally, the definition of auxiliary bodies, a meta-decision method, and other administrative details of the decision-change body may render the programme too complex for timely implementation, especially if further theorised on instead of flexibly put to practice. This, however, does not preclude an immediate start of the programme.

7.3. Implementation Prospects

8. Conclusions and Call to Action

Global crises, such as climate change and ecological collapse, largely reflect ineffective decision-making at a global level. There currently is no meaningful focus on system change to stimulate fundamental or global transformations, including the declaration of a planetary state of emergency. We therefore questioned how a procedure for deciding on the required system change should be designed.

Alternative global decision-making procedures (such as world federalism) have garnered insufficient support. Meta-decision structures to decide on such alternatives (for example, academia) have not been completely successful and are not focusing on decision-making for system change.

We propose an improved meta-decision structure: Let independent experts in collective decision-making, including design processes and problem analysis, design a procedure to decide on the required system change. Auxiliary bodies would then be placed to protect the design process against pitfalls. The programme of decision and system change is defined as the design of a decision-making procedure (‘decision change’) followed by the collection of system-change proposals and the actual decision on system change. Notably, the experts do not decide on system change themselves. We argued that the decision-making body may be perceived as legitimate and that it may engender system change despite the opposition that is to be expected.

A single, global team, supported by an independent organisation, should conduct this programme. We call on individuals to form such a team and on independent organisations to support its formation. The team can facilitate decision change as a first step to system change that will hopefully keep the earth habitable.