Guest post: The challenge of consensus decision-making in UN climate negotiations – Carbon Brief

[ad_1]

At the final plenary meeting of the Dubai climate conference, COP28 president Dr Sultan Al Jaber declared that the package of key decisions taken in Dubai would be known as the “UAE consensus”.

This threw a spotlight on one of the quirks of the UN climate negotiations: that COP decisions are always adopted by consensus.

Unlike most other multilateral environmental conventions, there is no majority voting rule, not even a “last resort” one, that can be invoked if there is no consensus.

This is not due to an unusual choice by the climate regime’s architects, but rather to the failure of the countries involved to agree on how to take decisions, at the very start of the regime in the early 1990s – and ever since.

Consensus, thus, applies by default, rather than by design.

But there is more to this story: disagreement over decision-making rules has its origins not in disputes among lawyers, but rather in the deliberate strategy of obstructionist forces aiming to weaken the intergovernmental response to climate change.

How did this happen? And how has consensus decision-making played out over the decades?

Rules of procedure

The international climate regime was established under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC, or “Convention”), signed at the Rio Earth Summit in 1992.

This entered into force in 1994 and – under Article 7.3 of the Convention – one of the tasks for the very first “Conference of the Parties” (COP1), held in Berlin in 1995, was to adopt a set of “rules of procedure” for itself.

Moreover, according to Article 7.2k of the Convention, these rules had to be adopted by consensus.

Defining “rules of procedure” is usually relatively straightforward for new regimes: the rules set out rather standard requirements for matters such as election of chairpersons, asking for the floor in a plenary meeting, circulation of written proposals, provision of interpretation into UN languages, raising points of order and so on.

In terms of decision-making, UN rules of procedure typically establish that decisions should be taken by consensus, while defining a “last resort” voting majority that can be invoked in cases where “all efforts have been exhausted and no consensus reached”.

The draft rules of procedure were prepared by the climate secretariat for governments to work on in preparation for COP1. They were modelled on those of the 1987 Basel Convention on transboundary hazardous waste (the most recent relevant treaty), and other precedents, such as the treaties on combating ozone depletion and the UN general assembly (UNGA).

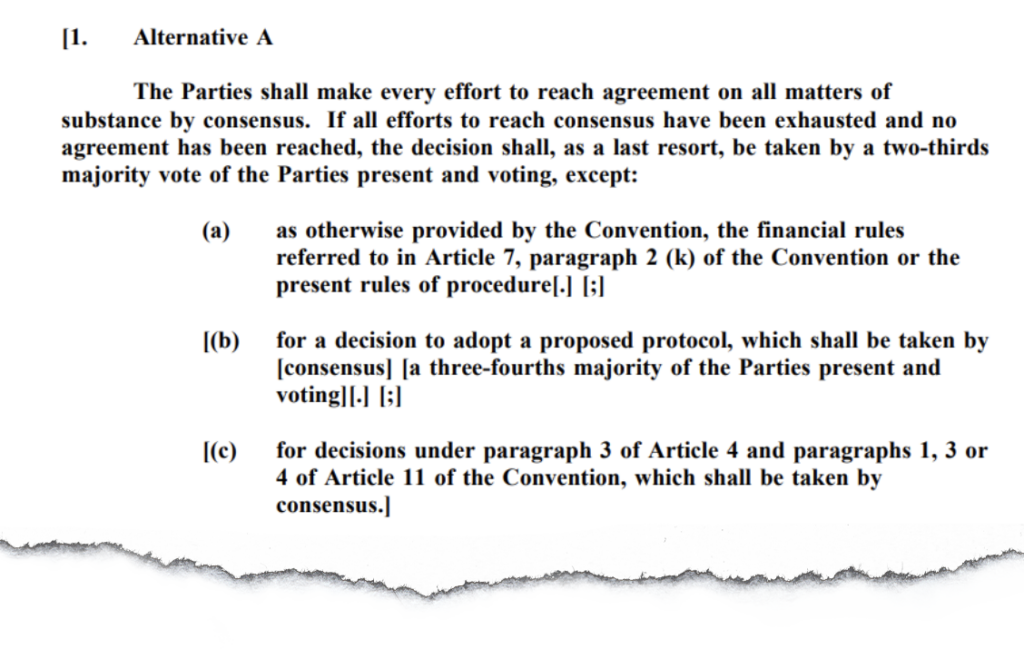

Draft rule 42 included provision for a two-thirds “last resort” voting majority which, like the rest of the draft rules of procedure, was unremarkable in the UN context.

The same “last resort” voting majority was in place – but never used – during the negotiation of the Convention itself in 1991-1992, when negotiators had drawn on UNGA procedures to structure their work.

Some political wranglings over the finer points of the rules of procedure were to be expected. But what should have been a rather routine matter escalated into a major political storm in the run-up to COP1, when members of the oil producers’ cartel the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) – principally Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, also Nigeria, Iran and others – began to argue that there should be no “last resort” voting rule at all. Instead they argued that substantive decisions should be taken only by consensus.

In insisting on consensus as the basis for substantive decisions, these oil exporting countries were receiving advice from US-based lobbyists with links to fossil fuel interests, automobile companies and libertarian political forces, notably the now-disbanded Global Climate Coalition, along with the Climate Council and its top lawyer the late Don Pearlman.

These lobbyists would openly pass notes to the Saudi or Kuwaiti delegations during plenary meetings, or even whisper in their ears (this was before mobile phones), prompting these delegates to raise objection after objection.

The interference from lobbyists became so brazen, that the chair of the negotiations in the run-up to COP1 in Berlin – Argentinian diplomat Raul Estrada Oyuela – banned anyone without a government badge from the plenary room floor, as he explained to me later. This ruling remained in place until the advent of mobile phones rendered it irrelevant.

Holding up rule 42

The disagreement over how general decision-making should take place within the COP process was not the only hold-up to the last-resort voting rule (42). There were wider disputes over climate finance, with donor countries – especially the US and France – insisting financial decisions should be taken by consensus, and developing countries wanting these to go to a vote.

Muddying the waters further, in a late move at the final negotiating session before COP1, OPEC proposed that the rules of procedure enshrine a dedicated seat for fossil fuel dependent countries on the influential committee, the COP bureau. This would match the seat already granted to small island developing states on account of their vulnerability (rule 22).

(This issue was, in the end, resolved through an informal understanding that fossil fuel dependent countries would always have a seat on the bureau, but through one of their traditional regional groups (usually Asia), rather than dedicated representation.)

Recognising that the Convention by itself was too weak to solve climate change, negotiators included a clause in the treaty calling for a “review” of the “adequacy” of developed country commitments at COP 1 (Article 4.2(d)). As COP 1 opened, there was “general agreement” that those commitments were indeed “inadequate”, although no consensus over what should be done about it. But one of the main options on the table was to launch a new round of negotiations on a stronger treaty, most likely a protocol.

The Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) and Germany had in fact already tabled draft protocols, including legally binding emission targets for developed countries.

Faced with the prospect that a new round of negotiations might result in substantially stronger curbs on emissions, oil exporting countries and their backers were “determined” to shape decision-making rules at COP1, ensuring that any protocol could only be adopted by consensus. Writing at the time, lawyers Sebastian Oberthur and Hermann Ott explained that “by requiring a consensus for the adoption of protocols Saudi Arabia and Kuwait were determined to preserve their ability to block any strong international agreement”.

An impasse

Despite extensive diplomatic outreach in the run-up to Berlin, and the best efforts of COP president Angela Merkel, the standoff over the “last resort” voting rule (42) could not be resolved at COP1.

Emerging agreement that decisions on financial matters should be taken by a double majority of donor and recipient countries (a pragmatic solution applied in other intergovernmental forums) was blocked, because the US and some EU countries insisted on consensus for these issues.

In what has been described as a “tactical move”, given that it had zero chance of being accepted, OPEC countered that all decisions – including financial ones – should be taken by a three-fourths majority vote. This was popular with developing countries, but out of the question for donors, who would always be outvoted under such a rule. The result was an impasse.

Nearly 30 years on, the entire rules of procedure remain in draft form, although they are applied at each COP session, as if they were adopted.

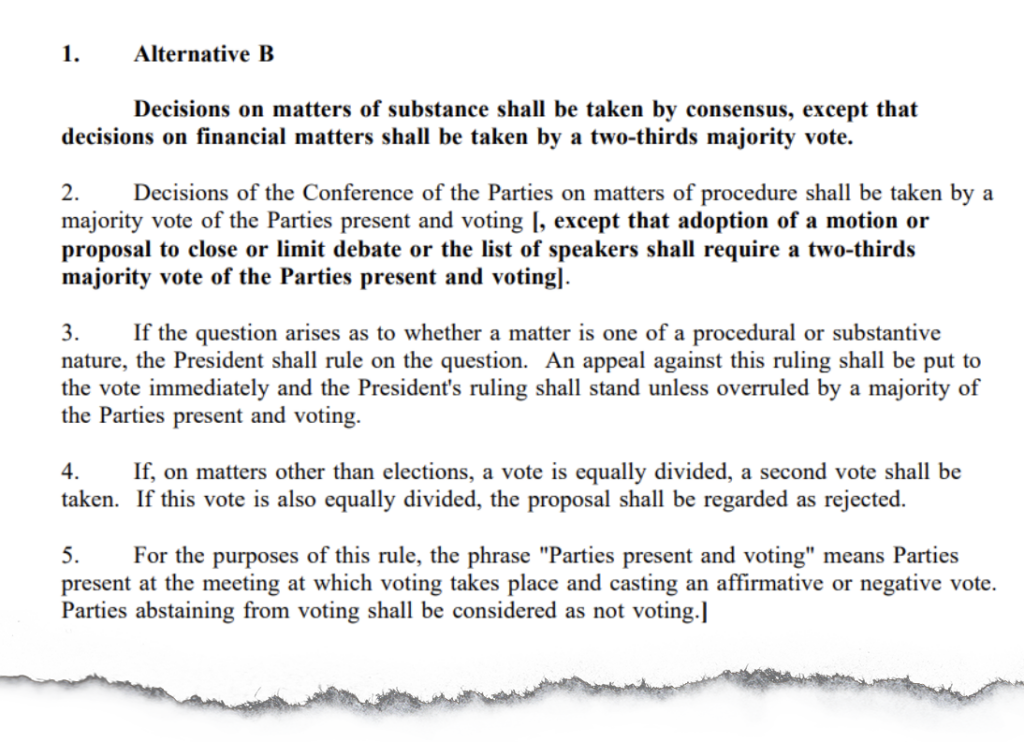

The exception is draft rule 42, which is not applied. The two main bracketed options – which signify they have not been agreed by all parties – for rule 42 are decision-making by consensus or consensus with a two-thirds “last resort” voting majority.

These have been frozen in time for the past three decades, with alternatives also for financial matters. But because no “last resort” voting rule has been agreed, the default is that decisions are indeed taken by consensus.

Consensus caveats

There is a caveat to the consensus imperative. Some decisions can, in fact, be taken by a majority vote.

The Convention, Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement can be amended with a three-quarters majority vote. This is because the Convention itself – articles 15 and 16 to be precise – rather than the unadopted rules of procedure, specifies this decision-making rule (and the other treaties apply the Convention’s rules).

Some matters set out in the rules of procedure can also be settled by voting, including challenges to a chair’s ruling on points of order that can be settled by a simple majority vote (rule 34) and the election of officers to the COP or equivalent bureau (rule 22).

Some chairs have occasionally threatened to take these procedural matters to the vote, but this has usually resulted in recalcitrant parties backing down.

A protracted dispute in May 2012 over who should chair the ad hoc group on the Durban Platform (ADP – the body that negotiated the Paris Agreement) for example, provoked South African ambassador Nozipho Joyce Mxakato-Diseko to threaten to call a vote. A solution was eventually found to appoint co-chairs, without a vote.

In a very small handful of cases, a procedural vote according to rule 34 has been called, in the form of a show of hands, but always in a subsidiary body or ad hoc group, and never in a COP.

The most high-profile case was in June 2013, during a lengthy debate over the SBI agenda. Faced with a point of order from the G77 and China, which called for substantive work to proceed, chair Tomasz Chruszczow (Poland) ruled interventions should continue. When the G77 and China challenged that ruling, chair Chruszczow called for a vote.

There are no formal records, and the SBI report omits any mention of it. But according to both the Earth Negotiations Bulletin and the Third World Network (p.49), abstentions were very widespread. The chair’s ruling stood and debate continued. It is likely that many delegations simply did not know what to do, so rare is the occurrence of voting.

Ironically, the debate was about a proposed new agenda item tabled by the Russian Federation, precisely on decision-making under the climate change regime.

There is one occasion when delegates did formally vote in the COP process, and on a decision with major substantive implications, but without reference to any rule.

This was at COP1 in Berlin, to decide on the permanent location of the secretariat. To overcome political sensitivities raging around the rules of procedure at the time, the exercise was labelled an “informal confidential survey”, rather than a vote.

Chair Estrada insisted it was “not a decision or a vote”, just a way of gauging preferences. But it was to all intents and purposes a secret ballot – and it did lead to a decision.

Three rounds of balloting eliminated the candidate cities of Montevideo in Uruguay, then Toronto in Canada, then Geneva in Switzerland, to leave Bonn in Germany victorious. This was, however, an isolated case that has not been repeated.

An added complication to decision-making in the climate regime is the absence of any operational definition of consensus.

Based on widespread practice elsewhere in the UN system, the term is generally taken to mean that there are no stated objections to a proposed decision. This understanding is included in the 2017 UNFCCC handbook for presiding officers, and echoes the custom whereby presidents and chairs, upon adopting a decision in plenary, bang their gavel and declare “I hear no objections, it is so decided”.

However, there is still ample room for interpretation. For example, can one objecting country really veto a decision that all other 197 parties want to see passed? This would equate consensus with unanimity, which many would contest. But if consensus does not equal unanimity, where does one draw the line? What if two countries are objecting, or even three? Does it matter who the countries are?

The history of the climate regime provides no simple answers, except to confirm that consensus is a messy process.

Challenging consensus

Challenges to consensus have produced different outcomes at different key moments in the negotiations.

The UNFCCC itself was adopted with a small handful of countries (mainly OPEC, plus Malaysia) waving their country nameplates in the air to raise objections. So was the Berlin Mandate, which launched negotiations on the Kyoto Protocol at COP1. Reservations were lodged to both documents.

At COP15 in Copenhagen in 2009, six countries declared their express opposition to the Copenhagen Accord, triggering the most dramatic plenary scenes ever seen in the climate negotiations, and preventing the document’s formal adoption.

The following year, in Cancún in Mexico, COP16 president Patricia Espinosa overruled Bolivia’s objection to the Cancún Agreements, declaring that “consensus does not mean unanimity… one delegation does not have the right to veto”. Two years later, in Doha in Qatar, COP18 president Al-Attiyah gavelled through the Doha Amendment to the Kyoto Protocol, ignoring an unmistakable request for the floor from Russia, supported by Belarus and Ukraine. In Paris in December 2015, COP21 president Laurent Fabius declared the Paris Agreement without acknowledging Nicaragua’s request to speak.

At COP24 in Katowice in Poland in 2018, three countries (Russia, Saudi Arabia and the US) refused to “welcome” the IPCC 1.5C special report, blocking the text. In Glasgow in 2021, language calling for the “phaseout” of coal was changed to “phase down” after a last-minute plenary huddle in response to objections principally from China, India, and South Africa. This provoked an outcry from Switzerland among others.

These differing outcomes and interpretations suggest consensus decision-making is an art, not a science. If nothing else, its ambiguous definition and reliance on the particular interpretation adopted by the chair generates far more uncertainty and potential for procedural dispute than if a voting rule could be invoked.

Unresolved items

“Adoption of the rules of procedure” – COP agenda sub-item 2(b) – is now the longest standing unresolved item on the COP agenda. Every year, the presidency undertakes to hold consultations on it, but these have now become almost perfunctory, with little expectation of progress.

There have occasionally been more serious moves to break the deadlock. At COP2 in 1996 in Geneva, the Zimbabwean COP presidency convened consultations that got as far as drawing up a compilation of options for rule 42.

This compilation included alternatives, for example, a seven-eighths supermajority. But countries maintained their positions at the following COP3 in Kyoto, and the deadlock continued.

In Durban, South Africa at COP17 in 2011, Papua New Guinea and Mexico made a concerted effort to resolve the impasse, in the wake of the highly-charged plenary dramas of Copenhagen and Cancún.

Their proposal took a novel approach: rather than trying to adopt the rules of procedure – which would require consensus – Papua New Guinea and Mexico proposed to amend the Convention itself, which could be done by a three-quarters majority, to introduce a voting rule.

The proposal had its challenges, notably that governments would have to individually ratify the amendment, potentially creating a confusing mosaic of parties and non-parties. But it did present a possible way forward that lawyers and negotiators could work with.

However, despite two rounds of extensive consultations at COP11 and COP12, the proposal never mustered sufficient support to progress. The agenda item under which it was considered – “proposal from Papua New Guinea and Mexico to amend articles 7 and 18 of the Convention” – remains on the provisional agenda to this day, although in abeyance (not discussed) since 2018.

There have been other attempts at a broader discussion of decision-making procedures. Following its overruling in Doha, the Russian Federation in 2013 insisted that procedural and legal issues relating to decision-making be subject to full-scale review, prompting the agenda fight at SBI38 discussed above.

After paralysing the SBI for an entire session, the issue was eventually added as a sub-item to the agenda of the subsequent Warsaw COP19. But little has come of it. Consultations on the sub-item are held every year but, like those on the adoption of the rules of procedure, have become purely a formality.

As discussed above therefore, there are three possible avenues for normalising decision-making rules on the COP agenda: sub-item 2(b) on adoption of the rules of procedure, the Papua New Guinea and Mexico proposal and the sub-item on decision-making under the UNFCCC process.

None of these options are subject to any serious consideration at present.

The main conclusion to be drawn from this, and from the extreme reluctance of parties to vote even on procedural matters, is that the consensus decision-making practice has, over time, become deeply entrenched in the climate regime.

The impact of consensus

What has been the impact of the consensus imperative on the climate regime? In the end, the absence of a voting rule did not prevent adoption of the key sets of commitments that built on the UNFCCC: the Kyoto Protocol, the Paris Agreement and their operational rulebooks.

Nonetheless, many would argue that consensus decision-making has led to slower, more incremental progress than under a last resort voting rule. However it is defined or interpreted, requiring consensus is a much more onerous bar to decision-making than a two-thirds, three-quarters or even seven-eighths voting majority would be.

Over the years, countless decisions have been abandoned, watered down or deferred to the next negotiating session because of a very small handful of objections.

At the opening plenary of COP27 in Sharm El Sheikh in 2022, the representative of Bangladesh argued that consensus was leading to “lowest common denominator” outcomes.

He added that “what we agree is going to be so weak, so ineffective, that it is not going to be anywhere near [meeting] the challenges of today”.

In the run-up to COP28 in Dubai in the United Arab Emirates in 2023, former US vice-president Al Gore denounced the absence of a voting rule, and the greater leverage this gives to obstructionists, as “absurd, ridiculous and offensive”.

The COP28 “UAE consensus” did not clearly call for the fossil fuel phaseout needed to limit warming to 1.5C, which may pay testimony to the limitations of consensus decision-making.

This is especially so if a very stringent interpretation of consensus is applied, in which, according to UNFCCC executive secretary Simon Steill, “all Parties must agree on every word, every comma, every full stop”.

With the entry into force of the Paris Agreement and adoption of its rulebook, the role of the COP is arguably increasingly shifting towards “political signalling”: sending out high-level messages to economic and political decision-makers of all kinds, on the direction, ambition and pace of global decarbonisation.

This underlines the need for COP decisions that are strong, unequivocal and aligned with the science. As such, it raises questions about the efficacy of consensus driven decision-making, and whether a “last resort” voting rule should be adopted for the climate change regime.

The Mexico and Papua New Guinea proposal demonstrated that creative legal options can be brought to the table. All that is needed – as ever in the climate space – is political will.

Sharelines from this story

[ad_2]