Skills use at work: Why does it matter and what influences it?

[ad_1]

By Glenda Quintini.

Skills policies have tended to focus disproportionately on the supply side – the acquisition and adaptation of skills. In recent years, however, there has been an increasing awareness that demand-side issues – how employers use skills in the workplace – are just as important as developing skills in the first place. It follows that supply-side interventions will not achieve the desired effects of raising productivity and economic growth unless they are accompanied by demand-side interventions. For example, a misalignment between the skills of the workforce and those required by employers could constrain innovation and hamper the adoption of new technologies.

This year’s OECD Employment Outlook – the organisation’s flagship publication on Employment issues, out yesterday– includes a chapter which shed light on the factors that are likely to influence the use at work of information processing skills – reading, writing, numeracy, ICT and problem solving. It uses information mainly drawn from the Survey of Adult Skills.

A key question is why employers do not always make full use of their workers’ skills. On the one hand, employers may not be fully aware of the skills possessed by new hires, leading them to select candidates on the basis of their qualifications. This issue was explored in detail in a previous edition of the OECD Employment Outlook (Chapter 5, EMO 2014) which highlighted how information asymmetries are particularly relevant for young people without work experience. In addition, this year’s chapter stresses how firms may lack the necessary internal flexibility to adapt job tasks to the skills of new hires or to put in place incentive mechanisms that may encourage workers to deploy more of their skills on the job. Similarly, skill requirements may change as a result of external factors such as the decision to offshore part of the production process and it may take considerable time to adapt the skill proficiency of the workforce to the firm’s changed demand for skills. Finally, labour and product market settings may influence the extent to which firms use the skills of existing employees and are able to adapt the workforce to changing skill requirements.

Country rankings by skill proficiency and skills use confirm that having a larger pool of highly proficient workers does not guarantee a more frequent use of these skills in the workplace. Only few countries have a similar ranking along the two scales. Seen from a different angle, the skills proficiency of workers explains only 1% to 6% of the variance in their skills use after accounting for workers’ occupation and firm characteristics.

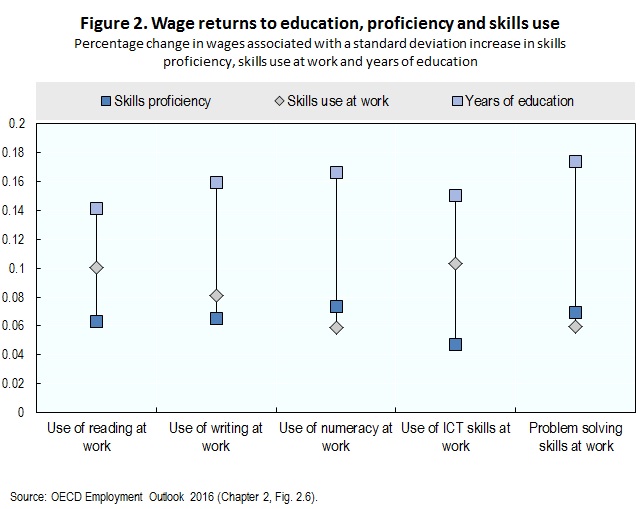

The chapter in this year’s Employment Outlook also explores the extent to which skills use at work matters for individuals and countries, over and above skill proficiency itself. For workers, higher skills use at work is associated with higher wages and higher job satisfaction. At the country level, the use of reading and writing skills correlates strongly with labour productivity. If Japan was able to bring skill use to the level of the US level, each worker would earn USD 680 more per year. If Italy was able to bring skills use to the level of Australia, workers would earn USD 2 000 more per year.

The chapter in this year’s Employment Outlook also explores the extent to which skills use at work matters for individuals and countries, over and above skill proficiency itself. For workers, higher skills use at work is associated with higher wages and higher job satisfaction. At the country level, the use of reading and writing skills correlates strongly with labour productivity. If Japan was able to bring skill use to the level of the US level, each worker would earn USD 680 more per year. If Italy was able to bring skills use to the level of Australia, workers would earn USD 2 000 more per year.

Given the importance of skills use at work, identifying practices and environments that might affect it is of crucial importance for firms and policy makers. Internally to the firm, high performance work practices (HPWP) – including work organisation and management practices – are positively related to the use of information-processing skills at work. They contribute to explaining between 14% and 27% of the variance in skills use across individuals (Figure 1). The way work is organised – the extent of team work, autonomy, task discretion, mentoring, job rotation and applying new learning – influences the degree of internal flexibility to adapt job tasks to the skills of new hires and promotes a better allocation of workforce to required tasks. Some management practices – bonus pay, training provision and flexibility in working hours – provide incentives for workers to deploy their skills at work more fully.

Skill requirements evolve also in response of global pressures and, in particular, to the offshoring of production. The evidence presented in the chapter suggests that industries in which the actual production is offshored to countries with low labour costs – so-called low-technology offshoring – use information-processing skills more intensively than industries retaining much of the actual production phase in the home country. This may be due to a shift of domestic activities towards high value-added tasks such as those involved in the research, innovation, design and marketing phases of production.

A number of labour market institutional settings are shown to influence the link between skill proficiency and skill use at work. For instance, strong collective bargaining institutions are found to be positively associated with the extent to which workers’ skills are used in the workplace. This finding is in line with evidence showing that good industrial relations institutions and practices, encouraging workers’ participation in their firms’ decisions, facilitate employees’ buy‑in to changes in work organisation and management practices associated with higher skills use.

This evidence on skill use at work and its determinants can inform the design of productivity and welfare-enhancing policies. Such evidence would clarify a number of issues, including the extent to which governments need to focus on: (i) protecting the potentially increasing number of workers left out of the labour market as a result of rapidly changing skill requirements; (ii) ensuring that skill formation policies account for these changes in employers’ skill needs; and (iii) encouraging firms to adopt management practices that make the most of existing skills.

Many countries have undertaken policy initiatives to promote better skills utilisation through workplace innovation. These initiatives recognise how a stronger focus on modern leadership and management practices in the workplace provides opportunities to better utilise existing skills, and that productivity gains can be achieved by engaging workers more fully. More concretely, many of these initiatives have focused on raising awareness about the benefits of better skills use, presenting HPWP as a win-win option for both employers and workers. Countries have also focused on disseminating good practice and sharing good advice, for example by identifying model firms. In some instances, funding is available for the development of diagnostic tools to help companies identify bottlenecks and measures that will promote a better use of the skills of their workforce. In the context of limited resources, SME’s with growth potential are often targeted on the grounds that smaller employers tend to find it more difficult/costly to adopt innovative work organisation practices.

Labour market polices can play an important role in reducing the impact of low-technology offshoring on workers displaced as a result of it – typically workers involved in routine tasks. Not only will these workers need access to unemployment benefits while looking for a new job, but many will also need to be retrained or upskilled so that they can be re-employed in higher value-added activities requiring different job-specific skills and higher information processing skills more generally than were required in their previous jobs.

Less actionable in terms of policy is the finding that labour market institutions may influence the extent to which employers make productive use of the skills of their workforce through their effect on labour costs. While institutions that raise labour costs are associated with better skill use, this potential benefit could be outweighed if there are substantial dis-employment effects.

[ad_2]