Taking a place-based approach to employment and skills strategies

[ad_1]

By Jonathan Barr.

Across the OECD, efforts are being taken to boost overall growth and investment. A skilled workforce represents a key marketing chip for local economies to attract investment and opportunity. However, efforts to boost job creation and employment can be undermined by potential skills mismatches or situations of low-skills equilibrium at the local level, which can be a trap that negatively impacts growth and the productive capacity of local economies (Job Creation and Local Economic Development, OECD, 2014). When the overall level of skills is low and employers operate on a business model that emphasises standard production and/or poor quality work, there are limited incentives to update skills or move to high-value-added strategies.

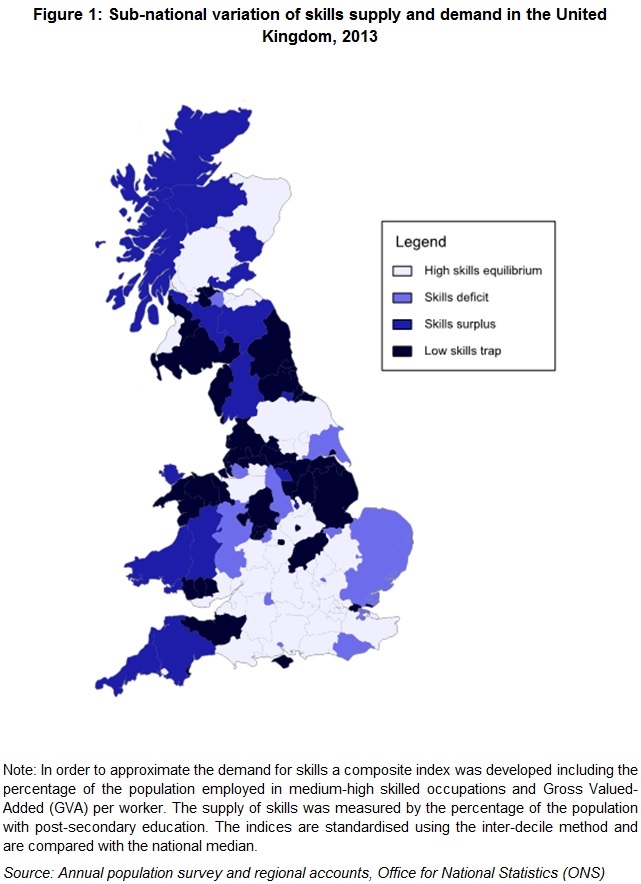

In every OECD country, one can see variations in the level of skill supply (e.g. the level of education) and the intensity to which employers are utilising and demanding skills in the local economy (data for each OECD country will be available in the forthcoming OECD publication Job Creation and Local Economic Development, 2016). Figure 1 shows the balance of the supply and demand of skills across the U.K. An interesting picture emerges which shows Northern regions in the U.K. more likely to fall into a low-skills trap versus those in the South which are more likely to be within a high-skills equilibrium (for further details see Employment and Skills Strategies in England, United Kingdom, OECD, 2015).

These regional variations in the supply and demand of skills mean that local level actors need to be equipped with the right tools and capacities to develop innovative employment and job creation strategies tailored to their local conditions. Partnerships are being used as a key governance tool across the OECD to better connect local leaders, who can leverage their resources, expertise, and knowledge to develop place-based responses to structural adjustment, local economic development, and productivity.

In the United States, there are about 600 Workforce Investment Boards (WIB), which take an active role in the management of employment and training programmes (Employment and Skills Strategies in the United States, OECD, 2014). Local WIBs are governed by a board comprised of business and civic leaders as well as social economy organisations, educational agencies and labour groups. Federal legislation requires at least 51% of the board members to be business leaders so that the needs of businesses are readily taken into account in designing and delivering employment services.

In Ireland, 16 Education and Training Boards have been set-up at the regional level to manage and operate secondary level schools, further education colleges, multi-faith community national schools and a range of adult and further education centres delivering education and training programmes (Employment and Skills Strategies in Ireland, OECD, 2014). Each board represents a catchment area of two to three counties, comprising 21 members, at least one of whom is an employer.

Local governance platforms that play a role in steering employment and skills policies exist in many other OECD countries, such as Canada, the Czech Republic, Korea, and the United Kingdom.

The OECD Reviews on Local Job Creation (2015) have demonstrated that partnerships require a degree of flexibility in the implementation of national policies to be successful. In this case, flexibility relates to the extent to which local employment services and training providers have the ability to adjust policies at their various design, implementation and delivery stages. It means that national policies need to give sufficient latitude when allocating responsibilities in the fields of designing policies and programmes; managing budgets; setting performance targets; deciding on eligibility; and outsourcing services.

The difficulty of injecting flexibility is to do so in a way that continues to meet national policy goals, while ensuring equity in service delivery and accountability. Flexibility should not come at the expense of a reduction in overall employment policy effectiveness. Furthermore, local capacities also need to be considered when granting additional flexibility to local employment and training agencies. When capacities are low and flexibility is high, policies and programmes may not be implemented in an efficient manner.

A number of different mechanisms can allow for greater differentiation in the utilisation of programmes and services locally, while continuing to meet national policy goals. For example, management by objectives systems can be used to achieve this, notably, by allowing for targets to be negotiated between the central and the local level, with the national level verifying that the sum of all local targets meets national policy goals. Funding policies can be made more flexible by allowing a certain percentage of overall funding to be used for local programmes, when designed in partnership with other stakeholders. Lastly, in any flexible system, local labour market information and intelligence is important as the “glue” that brings partners together to agree on common objectives and action.

[ad_2]