Community-Based Approach for Reporting Back Exposure Results in an Agricultural Community

[ad_1]

By Sara Amolegbe

One of the challenges in doing community-based participatory research (CBPR) is deciding how to best depict and disseminate research findings to study participants in a manner that is informative and culturally sensitive. A recent NIEHS-funded study, led by Beti Thompson, Ph.D., and Elaine Faustman, Ph.D., at the University of Washington provides insight about ways to work with culturally diverse communities to break down language and other barriers when reporting back exposures to study participants.

The researchers studied exposure to pesticides in an agricultural community in the Lower Yakima Valley of Washington state and identified pathways of exposure and seasonal variabilities in exposure for farmworkers, non-farmworkers, and children in the area. They found that both farmworker and non-farmworker families in this region had higher than average levels of pesticide exposure compared to the rest of the U.S. population.

As part of the research in the Yakima Valley, researchers measured pesticide levels in the participants’ urine as well as cholinesterase levels, which can be inhibited by exposure to pesticides. In Washington state, a 20 percent decrease in cholinesterase levels from the employee’s baseline level requires the employer to take action for employee safety.

(Photo courtesy of Branislav Pudar/Shutterstock.com)

After they made these discoveries, the scientists asked for feedback from community members on how to explain these results. In a recent paper, they examined the impact of their method to report back individual exposure data and found that their final design was effective in explaining complicated study results to participants.

“We knew that the community was very receptive to our work, but this is a difficult topic to provide information about so we had concerns about whether people were understanding our findings,” Thompson said. “This study shows that people not only understood the outcomes of the study, but they also remembered the findings and took action to address the outcomes.”

Community feedback informs dissemination methods

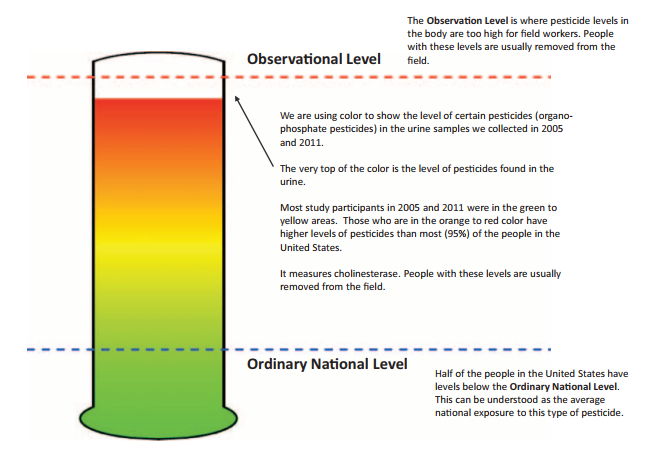

The researchers held a community forum to discuss how they should disseminate findings. The community members were unanimous in their response that a thermometer visual with a color gradient was the best way to show where each participant fell in terms of exposure and how their urinary metabolite levels compared to the average levels in the U.S. population. The researchers used community feedback to refine the visual so that it better explained the pesticide results.

With community input, the researchers decided to use a thermometer visual with a color gradient to explain individual exposure results. (Reprinted from J Occup Environ Med, doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000001107 [Online 10 July 2017], with permission of Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.)

The research team created a training manual that promotores, or community-based health promoters, could use to provide individual results during visits. The manual also included materials containing information about actions people can take to reduce their exposure to pesticides.

“Most of the individuals in the study were monolingual Spanish speakers, and we learned from community members that they would be much more comfortable talking to someone who spoke the same language and lived in the same community,” Thompson said. “Promotores were trusted people in the community who could convey the exposure results effectively.”

Examining the impact of disseminating results

Nine months after distributing individual study results of urinary pesticide metabolites, the researchers re-contacted 37 participants to see if the dissemination process had been effective. Study participants were interviewed by promotores about the process of distributing the study results and asked whether they recalled the visit from a health promoter to discuss their results.

Almost all the study participants recalled a home visit from a health promoter to discuss their pesticide levels, and more than three-quarters of participants correctly recalled that the health promoter used a thermometer graphic to explain the results.

A majority of participants recalled receiving the materials distributed at the first meeting, reviewing the materials, and sharing the materials with family, friends, and doctors. Most of the respondents also knew how to take measures to help protect themselves and their family from pesticide exposure, as indicated through their responses to questions about protective practices.

“This paper provides researchers with tools to translate complex information about exposure levels to their study population and a process for evaluating those tools,” said Faustman. “I’m working on a project with the World Health Organization on avoidable exposures, and I’m going to be using this paper to talk about some of the ways we convey complex information. This visual method also has global implications because it helps us think about how to convey exposure without language constraints.”

Involving communities from the beginning

“Nationally and globally, it is important that we keep people informed about research that affects them and make sure they are involved in the research process,” said Thompson.

Faustman pointed out an example of the effectiveness of CBPR research early in the project when they discussed their study design with community partners. “We had an elaborate diagram with potential routes of exposure and what we would sample in our study. The first thing we heard from the community was that everyone piles into the car, and we didn’t take car dust into account,” Faustman said. “Sampling the car dust and incorporating that immediately into the study design ended up helping us explain many of the observed exposure patterns.”

“As researchers, we go into communities around the world and assume we have the best science, but we are often humbled by the fact that our solutions are not easily implemented or may not even be important to those communities,” added Faustman. “We should be able to talk about what we study and get feedback from study participants.”

By involving community members in the entire process, from the study design all the way to the report back, all partners contributed expertise and shared decision-making and ownership.

Citation:

Thompson B, Carosso E, Griffith W, Workman T, Hohl S, Faustman E. 2017. Disseminating pesticide exposure results to farmworker and nonfarmworker families in an agricultural community: a community-based participatory research approach. J Occup Environ Med; doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001107 [Online 10 July 2017].

[ad_2]