1. Introduction

According to Maulik et al. [

1], the highest prevalence of people with an intellectual disability (ID) are seen in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC). Authors and researchers have continuously noted the scarcity of research on the African continent about people with ID compared to Western countries, e.g., [

2,

3,

4]. This dearth in research can be argued to be one of the sources of continued neglect, stigmatisation and limited care service provision for people with ID and their families (see [

3]). It has also been suggested that research on ID has enabled Western governments to create systems and structures that enable both government and private-funded social care provisions and improvements on the inclusion of people with ID in different parts of society, such as health, education, employment and housing [

3]. Some African countries such as South Africa seem to be carrying out more research about people with ID than other African countries such as Nigeria, which is the country of focus in the current scoping review. This was evidenced in a scoping review by Ngenga [

2], which found two out of the three papers to have met the criteria set in relation to people with ID to stem from South Africa and the third from Nigeria. Moreover, Capri et al. [

5] recently carried out a scoping review on the rights and citizenship of people with ID in South Africa and found 59 papers to be relevant.

In the absence of research on the prevalence of ID in Nigeria (see [

6]), it is not possible, other than through extrapolations from other countries, to estimate the overall number of people with ID [

4] (p. 88), [

6]. In 2018, the World Health Organization estimated that 29 million people in Nigeria were living with a disability [

7]. The lack of information, poverty, inconsistent assessment methods and possibly the desire of some families to hide such disabilities due to stigma and negative attitudes toward disabled people, e.g., [

4,

8,

9,

10], are likely to contribute to the continued neglect of issues affecting people with ID and their families. Nigeria is located in Western Africa, bordering the Gulf of Guinea, and is estimated to have a population of 219,460,000 people [

11]. The country is often described as the “Giant of Africa” due to having the largest economy in Sub-Saharan Africa, and it has a growing, relatively youthful population, where 62% are between the ages of 0 and 24 years [

11,

12]. Nigeria is ethnically and culturally diverse, with over 250 ethnic groups speaking over 500 languages [

10]; the main languages include English, Hausa, Yoruba and Igbo (Ibo), with Islam, Christianity and other religions being practiced in the country [

4,

11]. Although the country relies heavily on oil as its main source of foreign exchange earnings and government revenues, its economic growth has also been driven by growth in agriculture, telecommunications and services [

11].

Notwithstanding the country’s economic potential, the Nigerian National Bureau of Statistics’ “Poverty and Inequality in Nigeria 2019” report highlighted that 40% of the total population (almost 83 million people) live below the country’s poverty line of 137,430 naira (381.75 USD) per year [

8]. The association between poverty and disability has been repeatedly shown [

13,

14,

15], and Nigeria’s poorly funded, almost absent social welfare system means that most support for people with a range of disabilities is provided by families, the community or religious sources [

4].

Nigeria signed the United Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) and ratified its optional Protocol in 2010—an attempt to protect the rights of disabled people [

16] and, in January 2019, passed the Discrimination Against Persons with Disabilities (Prohibition) Act 2018 [

17]. However, Nigeria has yet to implement the adequate measures required to promote the legal rights of disabled people in all aspects of society [

16]. It has been argued, e.g., [

4,

18,

19], that stigma and negative attitudes towards disabled people in countries such as Nigeria are often due to a public lack of awareness and understanding of the causes of disabilities. This lack of understanding and awareness affects the treatment and care of people with disabilities in Nigeria. As a signatory of the UNCRPD, the country is obliged to maintain the rights and dignity of its disabled citizens, including those with ID, and therefore, it is crucial for more ID-focused research to inform and guide transformative interventions needed to improve the lives of people with ID in the country.

Within the range of disabilities (e.g., physical, sensory and intellectual), ID appears to be particularly “hidden” in communities, policies and research. Scior et al. [

20] argued that, globally, people with ID are the most abused, stigmatised, marginalised and socially excluded (also see [

21]). For example, a recent survey conducted in Northern Nigeria [

22] used local community-based and disabled people’s organisations in five administrative regions to contact disabled people in their communities. The majority of the 1067 respondents reported that they had physical, hearing or visual disabilities, and only 0.3% of the respondents were identified as having the characteristics of ID using the Washington Group Extended Set on Functioning questionnaire [

23].

The literature has consistently acknowledged the scarcity of information and empirical research about people with ID in developing countries such as Nigeria, e.g., [

2,

4,

24]. For example, a recent meta-synthesis [

6] of disability research in Western Africa revealed that, of the 223 disability articles from West Africa reviewed, only 24 were papers related to people with ID in the whole of West Africa; however, there was no information from the meta-synthesis on how several of these 24 ID studies were specifically derived from Nigeria [

6]. To our knowledge, there has been no published scoping review on ID research in Nigeria.

Research Question and Objectives

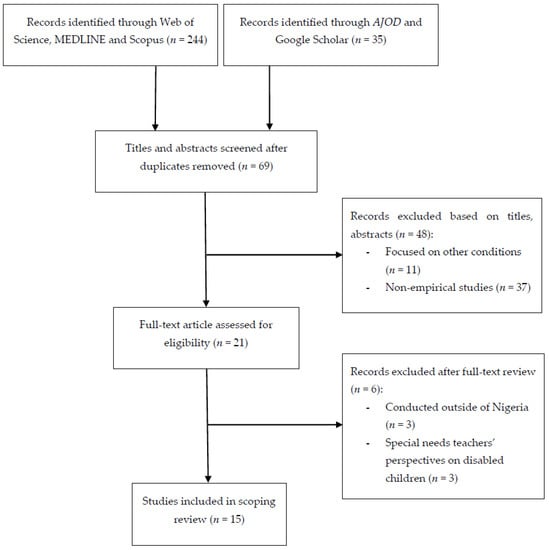

The present study describes a scoping review of empirical research about people with ID in Nigeria to explore evidence about their lives and identify gaps in their knowledge and/or practice. The following research question was formulated: What is known from empirical studies (published between January 2007 and March 2021) about the lives of people with ID in Nigeria?

4. Discussion

This scoping review aimed to locate articles reporting empirical research about people with ID in Nigeria in order to explore evidence about their lives and identify gaps in knowledge and/or practice. Fifteen studies met the inclusion criteria. The findings from the fifteen included studies reported the experiences and living conditions of people with ID and their families in Nigeria. Four themes were found from the papers that met the inclusion criteria of this scoping review. These themes related to:

-

the experiences of caregivers supporting a family member with ID;

-

the presence of additional neurodevelopmental and behavioural difficulties dis-played by children and young participants with ID;

-

the sexual activities of participants with ID;

-

English language comprehension, social skills and the need for entrepreneurial skills of young people with ID in Nigeria.

Personal accounts indicated that the negative experiences of families and people with ID are due to stigma, as well as a lack of public awareness and understanding of the causes of intellectual disability [

28,

30,

31]. These findings corroborated previous works on disabilities in lower- and middle-income countries, e.g., [

4,

9,

18,

19,

20]. The consequences associated with these negative experiences and attitudes regarding persons with ID and their families, e.g., [

28,

30,

31], include exclusion from various aspects of society, limited access to economic resources and inadequate, unaffordable health and social care. For example, Adeniyi and Adeniyi [

44] reported a scarcity of services for children with developmental disorders in African countries such as Nigeria and that the few available services are limited to the capital cities, provided by the private sector, expensive and beyond the affordability of most families.

The following [

28,

30,

32] found that parents adopted either “problem-focused or emotion-focused” coping mechanisms; with some parents acting as if the child with ID does not exist and hiding family members with ID from the public due to stigma, shame and negative attitudes from others [

32]. These findings support those of McConkey et al. [

9] that shame is often associated with ID in developing countries where families may hide their family member with ID due to physical impairments or behavioural challenges. These actions, according to McConkey et al. [

9], support the negative perceptions and misunderstandings of disabilities in societies. Therefore, families can play a key role in countering negative attitudes towards persons with ID through the “nurturing development” of their family member with ID and participating in family and community events. This places a significant burden upon families to “shoulder” the criticism from others, to bolster opportunities for contact and to establish relationships for people with ID within communities. Moreover, the suggestion that parents should be provided with “information” about what “causes” ID [

9] is supported by findings from this scoping review and can play a useful role in challenging the negative ideas of people with ID, as parents pass this information to others, especially in relation to their own family member with ID.

Other findings from this scoping review, e.g., [

28,

30,

32], reported families “accepting” their child with Down’s Syndrome and receiving support from other family members and being part of religious communities. Receiving such support was reported to protect parents of young people with ID from parenting stress.

This and other factors such as an emphasis on entrepreneurial skills suggest that, rather than be advised to repeat the services structure and interventions found in the Global North, countries such as Nigeria should look to the strengths of local spiritual and religious communities and traditional stakeholders, as well as disabled people and their families, for guidance on developing support services and interventions geared towards eradicating the stigma attached to people with a disability and their relatives. Despite Nigeria signing the UNRPD and passing the Discrimination Against Persons with Disabilities (Prohibition) Act 2018 in 2019 [

17], people with ID and their families continue to be disadvantaged, marginalised and “left behind” in government planning, with limited unaffordable services adding to parental anxiety related to the current and future prospects of family members with ID, e.g., [

28,

30,

31]. As discussed in Mostert [

45] and Scior et al. [

20], it is difficult, in practice, to implement the UNCRPD (or any laws) if the disability stigma in society is not addressed; it is therefore crucial for the government to work with national, regional, spiritual and religious, as well as local and traditional, groups; research centres and non-governmental disability organisations to counter the stigma towards people with ID (see [

10,

46]).

Although Nigeria is often described as the “Giant of Africa” due to having the largest economy in Sub-Saharan Africa, the included studies show that people with ID and their families continue to live in poverty and lack adequate health and social care services, along with resources to cater to their needs, e.g., [

37,

38,

39]. The association between poverty and disability is illustrated in people with a disability often being excluded from social, economic and political opportunities and bearing increased financial burdens related to their impairments. Poverty also means people experience limited access to adequate services, which comes with an added risk of illness, injury and impairment, leading to various disabilities, e.g., [

13,

14,

15,

47].

Other findings from this review, i.e., [

40,

41,

42,

43], reported that personalised learning strategies supported people with ID in gaining social and comprehension skills despite their parents’ economic and social status. In addition, entrepreneurial training and education was thought to improve the future economic prospects of people with ID [

43]. Therefore, these findings from this review suggest that skills training such as entrepreneurship might be helpful for people with ID, thus reflecting a source of self-employment and skills development that is rarely suggested in the Global North context, which tends to focus on people with ID being provided with support or access to existing work. The self-sufficiency implied by entrepreneurship presents a further potential strength of countries in the Global South.

This scoping review also reported research showing that people with ID were more sexually active, with multiple sex partners, have less knowledge of HIV and are less likely to practice safe sex (e.g., using condoms) than their peers without ID, which can be due to the lower availability of condoms and/or lack of sex education for people with ID, i.e., [

34,

35,

36]. These findings substantiate similar studies with disabled people that found that participants struggled to access sexual and reproductive health services due to cultural beliefs that they are not sexually active, e.g., [

21,

48,

49], despite being more likely to be a victim of sexual abuse [

22,

50] than their nondisabled peers.

The papers in this review mostly reported data from parents and siblings of people with ID as the participants; therefore, future research might need to include the voices of people with ID, who will be able to provide a more personal insight into their lived experiences in Nigeria. There also exists gaps in the topics studied, as seen by the current findings from this review. For example, there is a paucity of research about the social lives, sexuality and entrepreneurship training or ventures of people, especially adults, with ID. As a signatory of the UNCRPD, Nigeria has an obligation to encourage the rights and dignity of its citizens with disabilities, including those with ID, and it is important for the government to invest and fund disability research that will inform transformative change. A lack of such research limits the nation, as there is no reference point from which to develop the necessary services and interventions.

Limitations

A limitation of this review is the lack of quality appraisal of the papers included. Although scoping reviews do not aim to assess the quality of the evidence (see [

24]), in light of the emerging nature of ID research in Nigeria, we did not carry out one, because we wanted to be able to access the available studies relevant for this scoping review notwithstanding their methodological strength and rigor. We acknowledge and corroborate McKenzie, McConkey and Adnams’ [

3] recommendation that there is a need for improvement in “disability data collection” in Africa in the context of reporting, methodological rigor and robustness. The findings from the included literature that met the inclusion criteria for this review are not readily generalisable to the circumstances of all people with ID in Nigeria, as the studies are localised within single states and rarely include voices of children, young people and adults with ID.

The limited scientific quality of the research and reporting found in some of the papers included in this review suggests that additional support and resources need to be found to develop the potential for research to illuminate the living experiences and extent of these in the Global South, including Nigeria. For example, in Olufemi, Favour and Olaosebikan [

43], it is unclear which aspect of their findings derive from pupils with ID or their teachers, as one sentence says the “respondents are students with intellectual disability” (pp. 666), yet the survey instrument shown (incompletely) asks for marital status, and on page 668, it is suggested that teachers and pupils provide the data. This study, i.e., [

43], is unclear in other aspects as well. One potential support for African researchers to improve the research base to aid policy development and service development can consist of a mentorship scheme between more established academics and upcoming academics in African universities and/or knowledge exchange programmes using a partnership model between African, American, United Kingdom and European universities.

Our team at Inergency is excited to announce our partnership with @Disasters Expo Europe, the leading event in disaster management.

Join us on the 15th &16th of May at the Messe Frankfurt to explore the latest solutions shaping disaster preparation, response and recovery.

To all our members, followers, and subscribers in the industry, This is YOUR opportunity to explore the intersection of sustainability and disaster management, connect with industry leaders, and stay at the forefront of emergency preparedness.

Don't miss out! Secure your complimentary tickets now and be part of the conversation driving innovation in disaster resilience. ➡️ https://lnkd.in/dNuzyQEh

And in case you missed it, here is our ultimate road trip playlist is the perfect mix of podcasts, and hidden gems that will keep you energized for the entire journey