This study examines the different dimensions of PF, as well as PSWB attributes. To achieve these goals, given the lack of knowledge about the current PF and PSWB profile of female POs, this study comprises two parts that complement each other.

4.1. Professional PO Training Courses

Regarding the first part, it was found that in the professional PO training courses, the average (i) agent is 25.94 years old, 164.00 cm tall, and 63.64 kg heavy; (ii) chief is 35.89 years old, 162.28 cm tall, and 60.93 kg heavy; and (iii) officer is 26.00 years old, 166.00 cm tall and 62.97 kg heavy. Of these variables, age stands out as being significantly higher among chiefs.

It was also found that the distribution of PF and PSWB attributes is not the same among women from different professional PO training courses.

In the morphological attributes, the significant difference found in height and waist-to-hip ratio is noticeable. Regarding height, the women in the officers’ training course have a higher average height. However, according to Seidell et al. [

20], it is important to note that the waist-to-hip ratio may not be an accurate measure of visceral fat, as hip circumference includes other structures such as bone, gluteal muscle, and gluteal subcutaneous fat. For this reason, the same authors believe that waist circumference may be a more useful measure of abdominal fat.

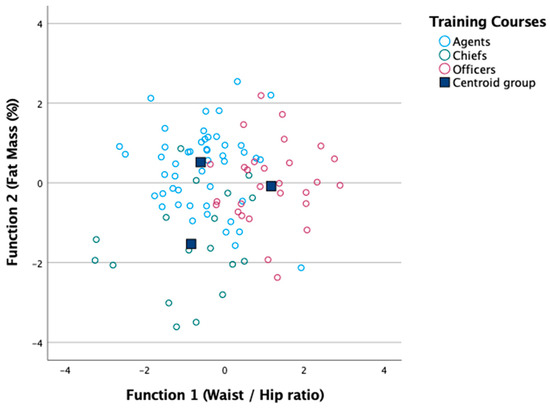

The women in the officer training course have higher waist-to-hip ratio scores compared to the other participants, which can be attributed to their high waist circumference and lower hip circumference scores. Similarly, they are the ones who have a higher hip circumference (71.59 cm). Although a higher waist circumference may imply a higher level of abdominal fat, in the present case it is not the women who have higher waist circumference values that have higher relative fat mass values. This situation may be explained by the distribution of body fat, which cannot be measured without appropriate equipment. The first discriminant function, defined by waist-to-hip ratio and waist-to-height ratio, explains 61.8% of the differences observed between the three professional POs training groups, while the second discriminant function, defined by relative fat mass and relative muscle mass, explains 38.2%.

A person’s body composition is another method of assessing a person’s PF, often used as an indicator of a person’s overall health and as a predictor of functional ability [

21]. Dawes et al. [

22] concluded that a higher-than-normal relative fat mass negatively affects POs performance in ground arm extensions, vertical jump, and aerobic capacity compared to POs who have a lower percentage (this is because body fat can increase resistance to oxygen flow and impair muscle oxygen-carrying capacity). Also, the results of studies conducted in elite units [

7,

23] showed that POs who belong to these units have a lower percentage of fat mass than other colleagues and fellow citizens. Nevertheless, body composition is determined by lifestyle and genetics, and the dimorphism between male and female body composition is evident from an early age and throughout all stages of human development, becoming more apparent in adulthood [

21,

24]. In general, females have more fat mass and less lean mass than males, mainly due to the effect of sex hormones on each sex [

21,

24,

25].

Also regarding age, Kukić et al. [

21] conducted a study with the aim of understanding whether there are significant differences in body composition between female POs of different ages, finding an increase in body mass index values, i.e., as people age, not only women but also men, tend to lose lean mass, resulting in a loss of strength, power, speed, flexibility, and cardiorespiratory capacity [

25]. Given the indirect relationship that appears to exist between age and PF, POs must strive to maintain their level of PF as they age [

4].

In terms of fitness attributes, it was found that (i) the women in the officers’ training course perform the highest number of repetitions of push-ups and have a superior performance in horizontal jump; (ii) it is the women in the chiefs training course who perform the highest number of sit-ups and run the 1000 m in the shortest time (and as a result of this finding, they have better predicted VO2max values).

Of the four studied fitness attributes, a very significant difference was found in the horizontal jump. This fitness test evaluates lower limb strength and is related to the leg strength and height of the individual [

26], i.e., it seems that leg muscle strength contribution is 9.24% and height contribution is 22.75% [

26]. In the situation in question, we found higher average body size and better results in the horizontal jump in females from the officers’ training course.

The cardiorespiratory fitness is also considered an important parameter for police professionals’ health [

3]. This consists of the body’s ability to continuously perform the same task through the intake and use of oxygen [

2], and oxygen consumption (

VO

2max) is one of the most used measures for this criterion [

3]. Maupin et al. [

3] found that POs who belong to an elite force have a higher relative

VO

2max compared to other POs and fellow citizens.

When looking at the PSWB attribute, it is possible to see if there are differences between the three professional PO training courses. The average scores of the GRIT-S reflect that the women in the officers’ training course have higher average Grit scores than the women in the agents’ and chiefs’ training courses. Comparing the three groups, women from the officers’ training course presented higher scores in the “perseverance in the effort”, the difference of which is significant for the average of the agents’ and chiefs’ groups.

A study by Alhadabi and Karpinski [

27], which examined the relationship between Grit level and the academic performance of university students, found that the Grit dimension, particularly the “perseverance in the effort”, had a positive impact on students’ autonomy and, consequently, on the effort they invest in their goals and academic performance. In this way, we can reflect on the commitment that the women of the three professional PO training groups show to their current path and their future goals. In accordance, these results suggested that it is the average woman in the officers’ training course who exhibits greater determination and mastery of her goals.

As for DRS, the only variable expressed in the confrontation of scores between the three groups is “alienation”. Nevertheless, since this variable is a negative dimension, the higher the value, the greater the vulnerability to stress. In the present case, the women from the agents’ training course scored higher on average than the women from the other two professional PO training courses. Also, Lovering et al. [

19], in a study that examined the physical and mental attributes of military personnel, showed that recruits who scored high in the positive categories of the DRS and low in the negative categories entered the course with greater physical availability and mental resilience. Moreover, other research has shed light on the main stressors faced by POs. Le Scanff and Taugis [

28] identified key sources of stress, including PF, organizational situations, leadership, family, work, and media, among special units of the French police. Additionally, Tharion [

16] emphasized the significance of traits like grit, resilience, and perseverance in coping with work-related challenges, interpersonal relationships, and social pressures.

Considering the interconnectedness of PF and PSWB, it becomes crucial to address these factors to optimize the performance and overall health of female officers within the Portuguese PSP. The study’s findings showed significant differences in PF attributes across the professional PO training groups, with women in the officers’ course demonstrating higher scores in height and waist-to-hip ratio, and participants in the chiefs’ course excelling in sit-ups and the 1000 m run. Furthermore, PSWB attributes varied, with women in the officers’ course exhibiting more perseverance and commitment to their goals, while women in the agents’ course were more susceptible to stress.

PF is undeniably presented here as a factor closely intertwined with the PSWB of POs. The negative effects of situations such as sleep deprivation, inconsistent eating habits, and night work on POs PF are evident [

28]. Building on these findings, further research examining the relationship between PF and PSWB attributes can provide invaluable insights. Understanding how these elements interact and influence each other might provide a more comprehensive understanding of the overall well-being and resilience of female POs in the Portuguese Public Security Police (PSP). Such research can inform the development of holistic support programs that combine targeted physical training with psychosocial support to empower women POs and provide them with the tools to thrive in their demanding roles effectively. By examining the interrelationship between PF and PSWB attributes, we can promote a healthier and more resilient police force, ultimately enhancing Portuguese Public Security Police skills and their ability to serve and protect the community.

4.2. Professional PO Training Courses and Bodyguard Special Police Sub-Unit

In the second part of the study, it was found that, in terms of the age and body composition of the participants, the average woman in the professional PO training courses is 29.30 years old, has a height of 164.27 cm, and a body weight of 62.90 kg. On the other hand, the average woman belonging to special bodyguard police sub-unit has an average age of 46.25 years, a height of 164.26 cm, and a body mass of 62.53 kg. The age variable, which shows a very significant difference, can be explained by the difference between the stage of life in which the professional PO training courses are attended (beginning of the professional career) and the stage in which one enters the special bodyguard police sub-unit.

The distribution of morphological attributes is not the same between the studied groups, i.e., it is possible to verify that women from the special bodyguard police sub-unit have a significantly higher waist-to-hip ratio than the women from the professional PO training courses (0.75 vs. 0.71). In general, the average participant in this study has a lower mean waist-to-hip ratio compared with a sample of civilian women (0.79 ± 0.08) in the study by Seidell et al. [

20], whose aim was to define the contribution of various measures of body composition to the assessment of fat distribution and the determination of risk factors for cardiovascular disease. In the world of the police, it can be noted that the value obtained in the present study gives better values compared with those obtained in the study of Yates et al. [

29] on female POs in operational and administrative functions (0.88 ± 0.20 and 0.80 ± 0.07, respectively). Looking at the absolute values obtained, they show that the average waist circumference of the women in the special bodyguard police sub-unit is higher (73.83 vs. 70.44 cm). Nevertheless, both verified values are within the range indicated by the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) for women with a low health risk (70–89 cm) [

30].

It was also observed that the participants of the special bodyguard police sub-unit have better values in body mass index (BMI), relative fat mass, and relative muscle mass than the women from the professional PO training courses. This demonstrated that the morphological differences between the two groups do not correspond to the expectations resulting from the comparison carried out by Kukić et al. [

21] in female POs of different ages, which showed that there is an increase in fat mass with increasing age. On the other hand, this tendency is supported by Araujo et al. [

31], whose study of a Special Police Unit with an average age of 42.6 years shows that it is not possible to attribute the change in individual body composition to age. Since it is not possible to assess whether there was an increase in fat mass as a function of the age of the participants of the special bodyguard police sub-unit, only to note that the relative fat mass is lower compared to women in professional PO training courses (whose average age is lower), we tend to agree with Araujo et al. [

31] when they point out that the commitment that these women, belonging to an elite force, have in maintaining their PF may be an explanation for the difference. The assumption of Araujo et al. [

31] is supported by Teixeira et al. [

32], which shows that in male POs who do not belong to an elite unit, age has a detrimental effect on the morphological attributes.

Regarding BMI, women from the special bodyguard police sub-unit and professional PO training courses have lower values than most of the Portuguese population (23.18 vs. 23.22 vs. 25.8 kg/m

2, respectively), than an elite group in Portugal aged 28–55 years (23.18 vs. 23.22 vs. 26.6 kg/m

2, respectively), and similarly aged Portuguese male POs (23.18 vs. 23.22 vs. 27.76 kg/m

2, respectively) [

31,

32,

33]. According to the Expert Panel on the Identification, Assessment, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults, the average BMI of participants is considered normal (18.5–24.9 kg/m

2) [

30]. Nevertheless, a limitation of BMI is that it does not distinguish between fat, muscle, or bone mass, which can lead to errors in body composition assessment (as individuals with a lot of muscle mass can have a BMI > 30 kg/m

2 and not be obese) [

30].

Results showed a significant difference in sit-ups (62.33 vs. 53.01 repetitions), with women from the special bodyguard police sub-unit scoring higher. The scores are also higher in the other tests, except push-ups (it was the women in the professional PO training course who performed more repetitions, i.e., 38.20 vs. 39.49 repetitions). According to Lockie et al. [

34], the lower number of push-ups can be justified by the higher waist-to-hip ratio, because the higher the waist-to-hip ratio, the lower the number of repetitions of push-ups.

The protocol for the execution of push-ups and sit-ups used in the special bodyguard police sub-unit, which served as the basis for the study, provides for an execution time of 90 s. There do not appear to be any studies in the literature consulted whose evaluation data on female POs resulted from the use of the same protocol. Complementarily, given the scoring table used in the special bodyguard police sub-unit, and considering the average age of these participants (age, 46.29 years), 63.33 repetitions of sit-ups correspond to 19.50 values (range, 0 to 20), 38.20 push-ups correspond to 20 values (range, 0 to 20), and 4 min and 28 s in the 1000 m correspond to 20 values (range, 0 to 20). For the women in the professional POs training groups, whose average age is 27.86 years, 53.01 repetitions of sit-ups have 12 values (range, 0 to 20), 39.49 push-ups have 14.50 values (range, 0 to 20) and 4 min and 34 s in the 1000 m have 8 values (range, 0 to 20).

There is no consensus in the literature on whether strength is a variable that is negatively affected by age. Although several studies show that there is evidence of a decrease in muscle strength exercises with age, others state that there is no significant difference in women across age groups [

22,

31]. In accordance, the difference in the performance of the different tests can be attributed to several factors, such as (i) the level of physical condition; (ii) the type of training performed; and (iii) cultural or social factors that influence the level of physical activity [

5].

Regarding the 1000 m test, we are not aware of any studies that have used this protocol to evaluate aerobic capacity. Therefore, the values are compared with the classification table of the physical tests at the Special Police Unit and with the cut-off values for professional PO training courses in the Higher Institute of Police Science and Internal Security and Police Officer Academy, i.e., 4 min 35 s, and 5 min, respectively. According to the data, the mean value for both training institutes is above the cut-off value for this test. Complementarily, the prediction of the

V̇O

2max over 1000 m shows that the women of the special bodyguard police sub-unit obtained better results than the professional PO training group (56.84 vs. 55.99 mL/kg/min, respectively), although the difference is not significant. Furthermore, the predicted

V̇O

2max of the study participants is on average higher than that of elite POs in Portugal aged 29–55 years (50.1 mL/kg/min), and that of Portuguese male POs with a similar average age as the participants (37.1 mL/kg/min) [

31,

32]. In Riebe et al. [

30], (i) 56.84 mL/kg/min (value obtained by women from the special bodyguard police sub-unit) in the 40–49 years age group is in the 95th percentile and is considered higher; and (ii) 55.99 mL/kg/min (value obtained by women from professional PO training courses) in the 20–29 years category is in the 85th percentile and is considered excellent.

In continuation, comparing the GRIT-S test results between the two groups of women in our study, we can see that the average woman from the special bodyguard police sub-unit has higher scores in both categories than the average woman from the professional PO training courses (“persistence in the effort”, 4.29 vs. 4.24; “consistency of interest”, 4.00 vs. 3.89), and according to Duckworth and Quinn [

17], all participants scored high on the GRIT-S test, indicating that they are people with high levels of grit. In fact, in Duckworth and Quinn’s [

17] study which validated this instrument, responses were analysed by age group. Using the 45–54 years category (since the average age of participants in the special bodyguard police sub-unit is 46.29 years), we find that the women of the special bodyguard police sub-unit have higher scores in both the “persistence in effort” and “consistency of interest” categories than participants in Duckworth and Quinn’s study (4.29 vs. 3.8 and 4.00 vs. 3.0, respectively). Similarly, among participants in professional PO training courses (ages, 25–34 years), both scores are higher than among participants in Duckworth and Quinn’s [

17] study (“persistence of effort”, 4.24 vs. 3.6; “consistency of interest”, 3.89 vs. 2.9).

Concerning DRS-II, the present study shows that, compared to the scores of women from the professional PO training courses, the participants from special bodyguard police sub-unit have lower scores in the three positive categories of resilience/robustness and higher scores in the negative categories, except for the measure “stiffness” (2.71 vs. 3.01).

Because there were no significant differences in the PSWB attributes, logistic regression models were created only for the first two constructs (morphological model and fitness model). In accordance, the results of logistic regression showed that waist-to-hip ratio and sit-ups are the attributes that have the largest contribution to the probability of belonging to the special bodyguard police sub-unit. More specifically, the greater the waist-to-hip ratio and number of sit-up repetitions, the greater the probability of belonging to the special bodyguard police sub-unit group (however, this information must be interpreted with some caution given to the reduced sample of special bodyguard police sub-unit participants).

In sum, based on the observed findings, this study highlights (i) the potential benefits of continued monitoring and adaptation of training and support programs (which are crucial for promoting a resilient and effective police force, particularly for female POs in demanding law enforcement roles), and (ii) the practical implications for the Portuguese Public Security Police and other law enforcement agencies, emphasizing the importance of tailoring training programs to address specific fitness attributes and psychosocial aspects for each training course. Nevertheless, to enhance the validity of the study’s findings, it’s essential to acknowledge the limitations associated with the sample size and composition, i.e., that (i) the group sizes (i.e., agents, chiefs, officers) vary significantly, and this imbalance can affect the statistical analyses and the validity of group comparisons (balance across groups); (ii) the relatively small sample sizes for each group, conducting subgroup analyses (e.g., comparing PF or PSWB attributes within each training course) might be limited in statistical power (potential for subgroup analysis); and (iii) only eight participants from the special bodyguard police subunit is a very small sample size, and it may be challenging to draw robust conclusions about this group (the special bodyguard police sub-unit). Considering the limitations stated, it seems important to highlight that the results can be interpreted as indicative of trends or patterns within this specific sample rather than making broad generalizations about all female police officers.

Our team at Inergency is excited to announce our partnership with @Disasters Expo Europe, the leading event in disaster management.

Join us on the 15th &16th of May at the Messe Frankfurt to explore the latest solutions shaping disaster preparation, response and recovery.

To all our members, followers, and subscribers in the industry, This is YOUR opportunity to explore the intersection of sustainability and disaster management, connect with industry leaders, and stay at the forefront of emergency preparedness.

Don't miss out! Secure your complimentary tickets now and be part of the conversation driving innovation in disaster resilience. ➡️ https://lnkd.in/dNuzyQEh

And in case you missed it, here is our ultimate road trip playlist is the perfect mix of podcasts, and hidden gems that will keep you energized for the entire journey