1. Introduction

Over the past few decades, we have witnessed a rapid decline in many preventable diseases, including smallpox, measles, polio, diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, measles, mumps, rubella, rotavirus, and hepatitis-B. While many factors have influenced this process, without a doubt, one of the main reasons for such a decline is vaccinations [

1,

2,

3]. Consequently, vaccination has been defined as one of the greatest public health achievements of the 20th century, both in the United States and the rest of the world [

4,

5]. However, until recently, the only Nobel Prize for developing a virus vaccine was awarded in 1951 to Max Theiler for discovering an effective vaccine against yellow fever [

6]. Then, after more than 70 years, in 2023, another Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to biochemist Katalin Karikó and immunologist Drew Weissman for the discoveries that enabled the development of effective mRNA vaccines against COVID-19 [

7].

Despite all this, suspicions of vaccination are widely believed in many societies [

8,

9,

10,

11]. In fact, opposition to vaccination dates back to the origin of the first vaccine, i.e., the cowpox vaccination invented by Edward Jenner, which provoked heated sanitary, religious, scientific, and political objections. For example, while some people believed that because it came from an animal, it was ‘unchristian’ [

8]; others suggested that it would make people grow horns [

12]. Other objections resulted from general distrust towards the government and the mandatory character of vaccination, as many people believed that introducing unknown substances into one’s body should not be compulsory and violates personal liberty [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Consequently, Anti-Vaccination Leagues or Societies were formed in several countries, including the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom, to abolish compulsory vaccination and fight for personal freedom [

10,

11].

Unsurprisingly, similar arguments emerged during the discussion on the efficacy and safety of other vaccines, including diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis (DTP), and measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR). However, the anti-vax movement gained momentum in the late 1990s when doctor Andrew Wakefield published a paper claiming that there is a causal link between the MMR vaccine and autism [

13,

14,

15]. Some communities also claim that immunization programs are part of the United States and Israeli governments’ conspiracy aiming at sterilizing Muslim children [

16,

17]. Similar rumours concerning the polio vaccine occurred in some African and Asian countries, leading to a boycott of polio vaccination campaigns [

18,

19,

20]. Finally, some people raise concerns that the human papilloma virus (HPV) vaccination was designed to cause infertility and prevent overpopulation [

21,

22].

Unsurprisingly, several vaccine conspiracy theories flourished during the COVID-19 outbreak [

23,

24,

25]. At the same time, most people who oppose the COVID-19 vaccine refer either to the old argument that vaccinations violate human rights to autonomy and personal choice or raise concerns about its safety and efficacy, suggesting that the vaccines were developed too quickly and can lead to many adverse events [

26]. There is also a widespread belief that the new generation of mRNA vaccines contains toxic ingredients that can harm or kill people or were even designed for that purpose. Others suggest that the COVID-19 vaccine was intended to modify human DNA and cause infertility to decrease the population of the planet. Another theory claims that either the government or Bill Gates are using COVID-19 vaccines to implant microchips in humans to track and control people [

26,

27]. Finally, some minority groups, including the Nation of Islam, argued that vaccination is a part of systematic ‘medical racism’ aiming at sterilization of the Muslim community [

17,

28].

Although it is often suggested that people who support anti-vaccine conspiracy theories tend to be less educated and wealthy, religious, right-wing, and members of minority groups, their supporters come from across the social and political spectrums [

29,

30]. Moreover, while COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy especially is prevalent among the general public, research suggests that it is also high among healthcare workers and medical and healthcare students [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42]. The issue is of crucial importance because while healthcare workers’ attitudes may enhance the public’s willingness to vaccinate, if doctors exhibit insufficient knowledge or express vaccine hesitancy and do not educate their patients about vaccine recommendation and evidence-based information on its benefits for individual and public health, or even spread suspicions towards vaccines, they may hinder health policy aiming at fighting infectious diseases which are currently on the rise, including future epidemics, especially since people who believe in anti-vaccine conspiracy theories turn to the Internet and are less likely to rely on family physicians and follow recommended prevention strategies, such as practicing hand hygiene, wearing masks, keeping social distance, and getting tested and vaccinated [

43,

44,

45]. This is particularly important because Poland is among the countries with the lowest acceptance of vaccinations against COVID-19 [

46]. Similarly, the vaccination rate against influenza is systematically decreasing in Poland and is one of the lowest in Europe [

47], and the HPV vaccination coverage rate in the country does not exceed 15–20% [

48].

Thus, since medical universities are forges of future healthcare workers who should be able to communicate with their patients about vaccination, vaccine hesitancy, and vaccine conspiracy theories [

49,

50,

51], this study, therefore, seeks to explore future doctors’ attitudes towards anti-vaccine conspiracy theories. Although only recently several studies on Polish medical students’ COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy have been conducted [

52,

53,

54], they often focus on students’ knowledge and willingness to get vaccinated. However, while several factors that may influence such decision were identified, including poor knowledge, fear of vaccine side effects, or having contact with anti-vaccination propaganda, still, little is known about future doctors’ support for anti-vaccine conspiracy theories. Meanwhile, since in the future medical students will play a crucial role in prevention of infectious diseases and promotion of vaccinations, their vaccine hesitancy may affect their ability to mitigate patients’ concerns and the spread of vaccine negationism. Thus, we argue that while future doctors support vaccinations as an effective form of infectious diseases and their acceptance for vaccine negationism is low, still the level of vaccine hesitance is moderately high.

3. Results

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the study participants. Out of all 2321 medical students comprising the population, 441 participated by completing the survey, providing a response rate of 17.7%. The sample consisted of 270 women (65.7%) and 139 men (33.8%), all of Polish origin. While study participants represented various years of study, 57.2% were enrolled in their first or second year of study, whereas 42.8% studied in the third, fourth, or fifth year. Note that as we had information on the size of the population, i.e., the number of students studying in a consecutive year by field of study, we used this information to calculate weights that adjust for differences between the sample and the population in terms of both characteristics.

Most study participants lived in big towns with more than 500,000 inhabitants (40.9%) or in towns with fewer than 100,000 inhabitants (45%). While 28% of students declared that religion influences their life decisions and choices, 72% claimed that religion is irrelevant. A total of 21.7% of respondents reported being hospitalized within the past five years, and 33.3% suffered from some chronic disease. Slightly above 23% reported blood donation experience, and 27.7% were declared bone marrow donors. While nearly all students declared being vaccinated against COVID-19 (97.8%), fewer than half claimed receiving the flu vaccination (41.8%).

Most respondents described both their political attitudes and worldview beliefs as leftist (51.3% and 68.9%, respectively) or centre (35.8% and 19.5%, respectively), while approximately 12% defined themselves as rightist/conservative (12.9% and 11.7%, respectively).

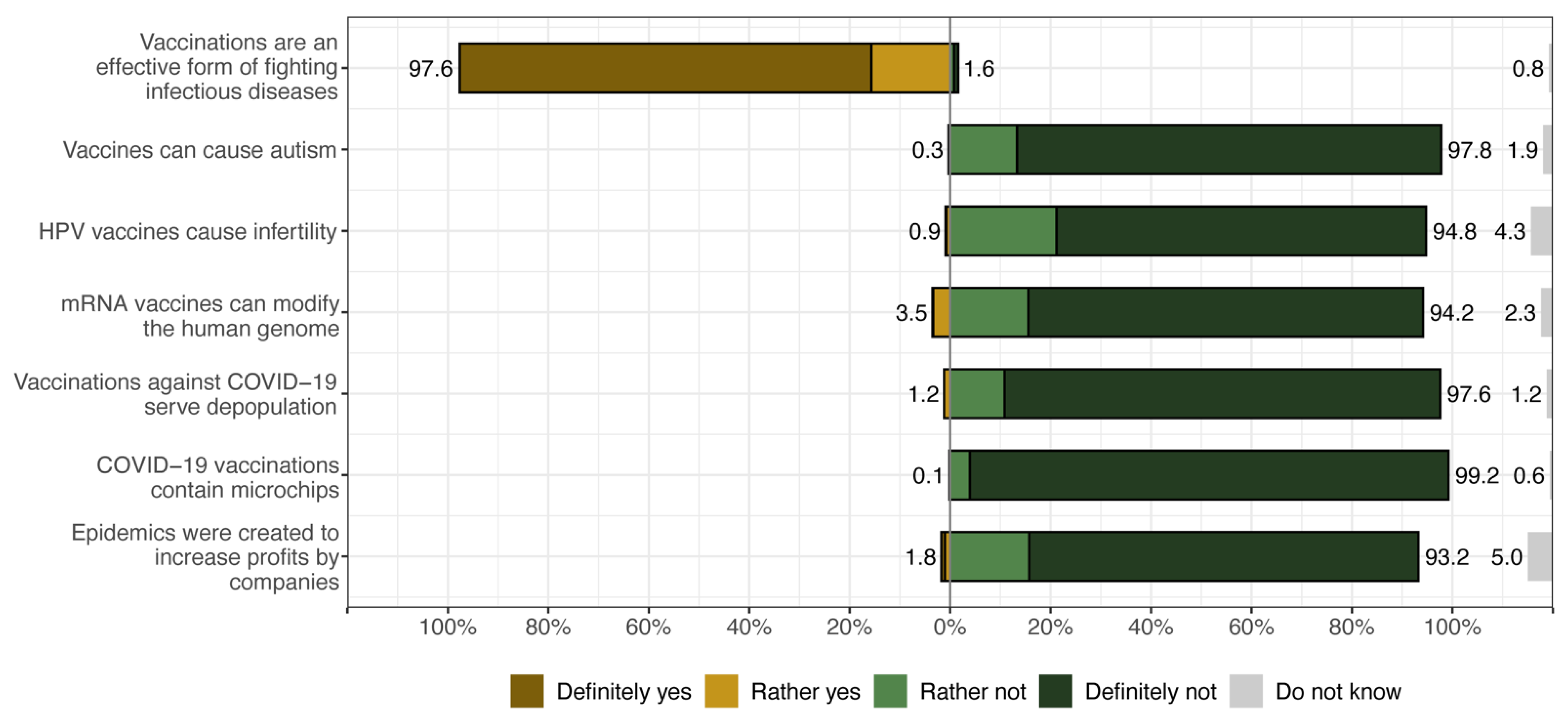

Our analysis begins with descriptive statistics examining the distribution of students’ beliefs in vaccine conspiracy theories. Note that study participants were presented with seven statements and asked whether they agreed or disagreed with them. The response options were in an agree–disagree format, namely ‘definitely not’, ‘rather not’, ‘rather yes’, and ‘definitely yes’, with additional ‘don’t know’ responses treated as the midpoint of a response scale. The first statement was general and measured whether students believed that (1) vaccinations are an effective form of fighting infectious diseases, while the remaining six statements described various specific vaccine conspiracy theories, i.e., that (2) vaccines can cause autism, (3) HPV vaccines cause infertility, (4) mRNA vaccines can alter the human genome, (5) vaccinations against COVID-19 are for depopulation, (6) COVID-19 vaccinations contain microchips, and (7) the Zika, Ebola, MERS, and SARS-CoV-2 epidemics were created to increase the profits of biotechnology companies.

Figure 1 shows the percentage of respondents who agree and disagree with the seven statements related to anti-vax conspiracy theories.

Figure 1.

Medical students’ support for anti-vax conspiracy theories.

Figure 1.

Medical students’ support for anti-vax conspiracy theories.

When analysing the survey responses regarding various vaccine-related beliefs presented in

Figure 1, it is clear that there is a widespread consensus among medical students regarding the effectiveness of vaccines in combating infectious diseases, with over 97% of respondents expressing that they ‘definitely’ or ‘somewhat’ believe in their effectiveness. Conversely, the same proportion of participants do not attribute a link between vaccines and autism, expressing a ‘definitely’ or ‘somewhat’ disagreement, and a similarly high proportion of medical students (over 90% in each case) do not attribute HPV and mRNA vaccines with altering the human genome and do not believe that COVID-19 vaccines are for depopulation, contain microchips and that epidemics such as Zika, Ebola, MERS, and SARS-CoV-2 were created to increase profits for biotechnology companies. However, even though the fraction of medical students who reported believing in anti-vax conspiracy theories is small, a non-negligible fraction of them ‘don’t know’ whether or not to accept conspiracy theories related to vaccinations.

Based on students’ ratings of whether they agreed or disagreed with the above statements, we constructed an index of support for anti-vax conspiracy theories. First, we dichotomized the ratings of the statements by contrasting those who answered ‘definitely yes’, ‘rather yes’, or ‘don’t know’ (score 1) with the rest of the respondents (score 0), except for the first statement, where we contrasted those who answered ‘definitely not’, ‘rather not’, or ‘don’t know’ (score 1) with the rest of the respondents (score 0). Thus, for each item, a score of 1 means that the respondent believes in a specific anti-vaccine conspiracy theory or does not believe in the efficacy of vaccination in controlling infectious diseases in general, and a score of 0 means the remaining counterpart. Second, for each respondent, we calculated the sum of the scores for each of the seven items; thus, the index ranges from 0 to 7 and counts how many anti-vax conspiracy theories students believe.

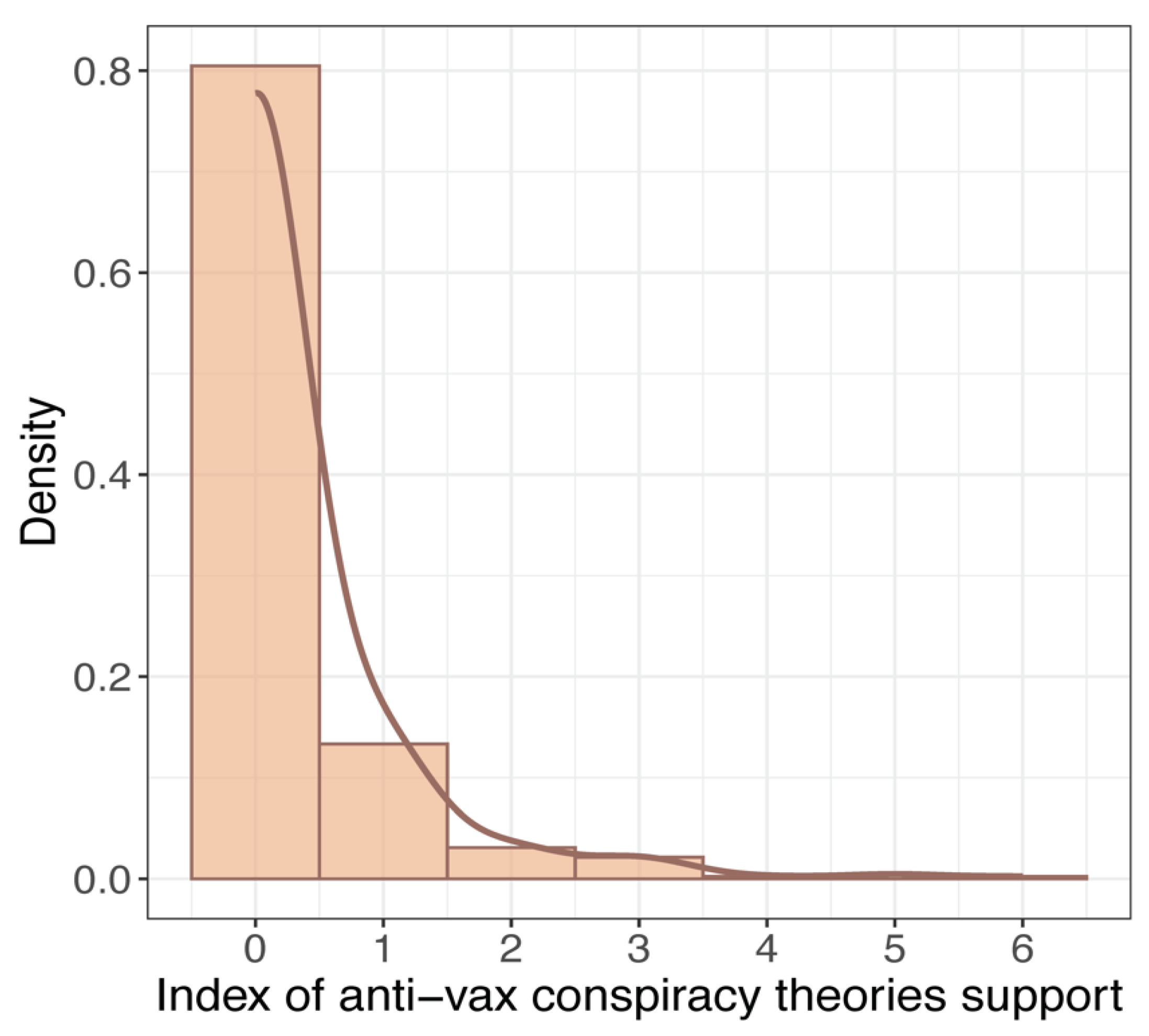

Figure 2 shows a histogram and density plot of the distribution of the index scores. Note that 80% of all study participants do not accept any anti-vax conspiracy theory, which means that 20% of medical students believe in at least one.

Figure 2.

Histogram and density plot for the index of support for anti-vax conspiracy theories.

Figure 2.

Histogram and density plot for the index of support for anti-vax conspiracy theories.

Figure 3 summarizes the results of five different reduced logistic models, with belief in anti-vax conspiracy theories as the dependent variable. All the covariates were added stepwise. Model 1 includes only flu vaccination, model 2 includes students’ medical history—hospitalization and suffering from chronic diseases, model 3 includes blood donation and bone marrow donation as covariates, model 4 includes the role of religion, and model 5 includes the political and normative orientation as the only covariate. In addition, the regression coefficients have been transformed using the exponential function; thus, a value greater than 1 (vertical dashed line) indicates that the predictor increases the likelihood of believing in anti-vax conspiracy theories. The shape of the points indicates whether the regression coefficient is statistically significant at

p p

The results of the reduced regressions demonstrate that medical students who reported not having had the flu vaccine were 2.2 times more likely to believe in anti-vax conspiracy theories than those who had had the flu vaccine. Similarly, those who declared they do not suffer from chronic disease and those who said they were not bone marrow donors as well as those who declared as politically right-wing and conservative were also significantly more likely to believe in anti-vax conspiracy theories. Conversely, students who reported they had not been hospitalized within the past five years and who declared that religion plays little or no role in their lives had significantly lower odds ratios of believing in anti-vax conspiracy theories compared to their religious counterparts.

Table 2 presents the results of the adjusted logistic regression models, i.e., with sociodemographic characteristics added to control for the relationships observed in reduced models (again, the regression coefficients were transformed to represent odds ratios for each explanatory variable). The table also includes information on whether the regression coefficients for the regression terms were statistically significant by reporting detailed

p-values, and we calculated standard errors for the following coefficients. In addition, we performed the likelihood ratio test (LRT) for each model to assess whether the model’s reduction in deviation was statistically significant compared to the null deviation. We found the reduction to be significant for each model (for details on the model fit statistics, see the

p-values obtained in the LRT test, along with the Akaike Information Criterion score and log-likelihood shown at the bottom of

Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of regression results for adjusted models.

Table 2.

Summary of regression results for adjusted models.

| Predictors |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

Model 4 |

Model 5 |

| OR (SE) |

p |

OR (SE) |

p |

OR (SE) |

p |

OR

(SE) |

p |

OR

(SE) |

p |

| Intercept |

0.30

(0.05) |

<0.001 |

0.54 (0.12) |

0.004 |

0.30 (0.07) |

<0.001 |

0.88 (0.15) |

0.448 |

0.41 (0.06) |

<0.001 |

Gender: Male

[vs. Female] |

1.25 (0.17) |

0.110 |

1.12 (0.16) |

0.418 |

1.10 (0.17) |

0.189 |

1.17 (0.16) |

0.267 |

1.04 (0.15) |

0.798 |

Year of study 3–5

[vs. 1–2] |

0.48 (0.10) |

0.001 |

0.44 (0.06) |

<0.001 |

0.52 (0.07) |

<0.001 |

0.43 (0.06) |

<0.001 |

0.40 (0.05) |

<0.001 |

Domicile: 10–100 k

[vs. Up to 10 k] inhabitants |

0.56 (0.10) |

0.001 |

0.52 (0.09) |

<0.001 |

0.53 (0.09) |

<0.001 |

0.48 (0.09) |

<0.001 |

0.50 (0.09) |

<0.001 |

Domicile: 100–500 k

[vs. Up to 10k] inhabitants |

0.67 (0.14) |

0.058 |

0.62 (0.13) |

0.026 |

0.65 (0.14) |

0.039 |

0.73 (0.15) |

0.131 |

0.70 (0.15) |

0.085 |

Domicile: <500 k

[vs. Up to 10 k] inhabitants |

0.38 (0.06) |

<0.001 |

0.36 (0.06) |

<0.001 |

0.38 (0.06) |

<0.001 |

0.39 (0.06) |

<0.001 |

0.39 (0.07) |

<0.001 |

| Received flu vaccination: No [vs. Yes] |

1.93

(0.27) |

<0.001 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hospitalized within

past five years: No [vs. Yes] |

|

|

0.59 (0.09) |

0.001 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Suffering from

chronic disease: No [vs. Yes] |

|

|

1.61 (0.25) |

0.002 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Blood

donor: No [vs. Yes] |

|

|

|

|

0.84 (0.14) |

0.322 |

|

|

|

|

| Declared bone marrow donor: No [vs. Yes] |

|

|

|

|

1.99 (0.36) |

<0.001 |

|

|

|

|

Role of religion:

Little/none [vs. Important] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.41 (0.06) |

<0.001 |

|

|

Right–conservative

[vs. Left–liberal] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3.06 (0.47) |

<0.001 |

| Observations |

401 |

401 |

401 |

401 |

401 |

Likelihood Ratio Test

(p-values) |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

| AIC |

1574.322 |

1582.870 |

1583.939 |

1555.988 |

1548.729 |

| log-Likelihood |

−780.161 |

−783.435 |

−783.969 |

−770.994 |

−767.364 |

Regarding Model 1, in which three sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents were included to control the effect of receiving a flu vaccination, we observed a significant relationship observed for this covariate. Moreover, when analysing regression coefficients for the socio-demographic variables, we noted that, on average, respondents in their 3rd to 5th year of study were significantly less likely to believe in anti-vax conspiracy theories (the odds ratio is slightly below 0.5; i.e., the propensity is halved compared to their counterparts in their 1st and 2nd year of study) (

Table S1 shows the percentage of students agreeing with each of the anti-vaccine theories by year of study).

Similarly, the tendency to believe in anti-vax conspiracy theories was also halved for respondents living in cities with between 10,001 and 100,000 inhabitants and even lower for those living in large cities (i.e., over 500,000 inhabitants) compared to the reference category, i.e., those living in a small area of residence (up to 10,000 inhabitants). At the same time, for those living in cities with between 100,001 and 500,000 inhabitants, the results were mixed and depended on the model applied. In addition, the regression results show that male and female respondents did not differ significantly, although male respondents were slightly more likely to believe in anti-vax conspiracy theories. Note that the associations for the control variables remain significant in all subsequent models.

In Model 2, respondents’ medical history (i.e., whether the student has been hospitalized in the past five years and has a chronic illness) was included in the regression along with the sociodemographic variables. We found evidence of a significant relationship between these two covariates and the dependent variable, as indicated by p-values below the critical level of 0.01. In turn, in Model 3, no evidence was found of a significant effect (at the p-level equal to 0.05) of blood or bone marrow donors, even though those who reported not being registered as bone marrow donors were found to support anti-vax conspiracy theories more than twice as often as those who reported being in a bone marrow donor registry.

Finally, Model 4 and Model 5 include the role of religion in life and political orientation as covariates, respectively. We found significant regression coefficients in both cases and the expected direction. Those who reported that religion plays little or no role in their lives have significantly lower odds ratios of believing in anti-vax conspiracy theories compared to medical students who said that religion plays an important role. On the other hand, students who identify themselves as politically right-wing and conservative are almost two and a half times more likely to believe in anti-vax conspiracy theories than students who identify themselves as politically left-wing and liberal in terms of norms and values.

4. Discussion

During the pandemic, numerous studies have delved into the reasons for the low interest of medical school students in vaccinations. Most of them did not explore the issue from the angle of conspiracy theories. However, results from various countries revealed that not all students and medical professionals were vaccinated or expressed intentions to be vaccinated [

68,

69]. In recent years, there has been growing concern about the impact of conspiracy theories, heightened further by the COVID-19 pandemic, especially during the first wave of novel coronavirus when, due to lockdowns, many people turned to the Internet and social media, which become their major source of information. However, it was shown that such platforms as Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube contributed significantly to the dissemination of COVID-19-related conspiracy theories, becoming a source of the ‘infodemic’ and mass suspicions about vaccination [

70,

71,

72,

73]. The outbreak has witnessed the widespread dissemination of numerous conspiracy theories, posing a potential threat to adherence to recommended preventive measures. Until November 30, 2020, Islam et al. identified 637 items of COVID-19 vaccine-related social media information, of which 91% were rumors and 9% were conspiracy theories [

26]. These items comprised news articles, social media narratives, online reports, and/or blogs that garnered approximately 103.3 million likes, shares, reactions with emojis, or retweets on social media.

The emergence of various conspiracy theories during the pandemic raises concerns, particularly due to documented evidence indicating their negative impact on vaccination intentions [

43,

73,

74,

75], even among healthcare workers [

31,

32,

33,

36,

37]. Mistrust in medical information was also a factor influencing this state of affairs, as indicated [

76]. For aspiring medical professionals, the situation is further complicated, as these conspiracy theories not only affect their personal vaccination decisions but also have the potential to influence how they approach persuading patients to get vaccinated. Finally, it is worth noting that conspiracy theories concern not only vaccinations, prompting questions about how a future doctor’s professional activities and beliefs can be influenced. This is even more important because in our study, almost 20% of medical students believe in at least one anti-vax conspiracy theory or were unsure.

While the majority of people in any country do not believe in misinformation about COVID-19, certain misinformation claims are consistently regarded as reliable by a significant portion of the public, posing a potential risk to public health. Importantly, a clear link has been demonstrated and replicated internationally, showing that susceptibility to misinformation is associated with vaccine hesitancy and a decreased likelihood of adhering to public health guidance [

77].

Research on medical students’ knowledge about vaccination indicates a generally moderate level of knowledge and positive attitudes, with identified gaps, especially in revaccination and flu vaccination [

38,

39,

40,

41]. These gaps suggest a need for additional education and training in these specific areas. The studies also underscore the influence of the year of study and experience in delivering immunizations on knowledge levels, hinting at the potential impact of targeted interventions in medical education [

42].

Our study found that the vast majority of medical students believe vaccinations are an effective means to combat infectious diseases. However, a small percentage (1.9%) in our surveyed group disagrees, and an even smaller percentage (0.6%) has no opinion on the matter. While these numbers represent only a handful of students in our sample, their very existence remains intriguing. It is noteworthy that such views also exist among medical specialists; Sule et al. identified 52 physicians in 28 different specialties involved in propagating COVID-19 misinformation [

78].

Consistent research findings indicate the detrimental impact of anti-vaccine conspiracy theories on vaccination intentions [

43]. However, this influence can differ across groups, as demonstrated by higher vaccination intentions among Polish medical students compared to their non-medical counterparts [

52]. Regardless of their major, Polish students exhibit considerable knowledge gaps in vaccination and require additional education on this subject. This knowledge deficit extends to the COVID-19 pandemic, where medical students display a greater willingness to receive the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine compared to other students [

68]. However, it is worth noting that Polish medical students exhibit a more positive attitude toward vaccination than nursing students [

53]. Jastrzębska et al.’s research results suggest that vaccination knowledge may not be optimal among Polish medical students [

54]. Our study findings further suggest a potential connection between belief in conspiracy theories and attitudes contrary to influenza vaccination. There is no such connection with COVID-19 vaccinations because students were obliged to be vaccinated during the pandemic, which resulted in an increase in the vaccination rate, probably sometimes against the wishes of the vaccinated themselves. Flu vaccinations are voluntary, and we are able to determine the relationship between vaccination and belief in conspiracy theories. The influenza vaccination rate in the study group was not high, but belief in one of the conspiracy theories seems to have figured heavily in the decision to get vaccinated against influenza or not.

During the COVID-19 pandemic in Poland, vaccine hesitancy was particularly pronounced among certain groups. Research and reports have indicated that vaccine hesitancy was prevalent in Poland, with some experts attributing it to decades of Communist rule that eroded public trust in state institutions. The country had one of the lowest rates of double-jabbed citizens in the European Union, and vaccine hesitancy was particularly pronounced in Central and Eastern Europe [

79].

Additionally, a study evaluating the approach towards vaccination against COVID-19 among the Polish population found that the rapid development of COVID-19 vaccines presented a significant challenge to their general acceptance, including in Poland. The study aimed to target groups of Polish citizens with the highest risk of vaccine hesitancy, indicating that certain segments of the population were more hesitant towards COVID-19 vaccination. Therefore, it can be inferred that vaccine hesitancy was prevalent among certain segments of the Polish population during the COVID-19 pandemic [

29].

While there is a common notion that individuals endorsing anti-vaccine conspiracy theories are typically less educated, religious, right-wing, or associated with minority groups, it is noteworthy that proponents of such theories come from various social and political backgrounds. Polish research, akin to studies from other countries, has highlighted the link between vaccine hesitancy and the influence of right-wing political ideologies opposing vaccination in diverse forms [

29,

30,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83], as well as religious beliefs [

30,

84]. The effect size of these findings is substantial and warrants significant consideration. Our study demonstrated that the surveyed group of medical students mirrors societal profiles in this regard; we also observed associations between belief in conspiracy theories, a heightened role of religion in individuals’ lives, and more frequent conservative political affiliations. Furthermore, attention should be drawn to the correlation between belief in conspiracy theories and being a bone marrow donor, as well as being free of chronic diseases; these results also exhibit a considerable effect size.

An earlier study [

85] demonstrated that students who declared having been exposed to information posted on social media suggesting not to receive the flu vaccination had a higher level of vaccine hesitancy. While Jamison et al. who analyzed 2000 most active Twitter accounts discussing vaccines, identified both vaccine opponents and proponents, they also found that 17% of them were bots [

86]. Simultaneously, 35.4% those who opposed vaccines shared unverifiable or even fake information, including anti-vax conspiracy theories, coronavirus myths, scams and rumors.

Previous studies have demonstrated that although vaccine sceptics and negationists constitute a minority among the public which in general favors benefits of vaccination, they exert a significant online presence, particularly on Twitter. In was also shown that in particular, messages on vaccines contribute to the dissemination of misinformation and disinformation on public health issues on social media [

87,

88]. Furthermore, vaccine skepticism and negationism is mainly spread by such threat actors as bots and state-sponsored trolls who were promoting vaccination misinformation in cyberspace even well before the COVID-19 outbreak [

86].

Twitter bots and trolls, particularly those associated with Russia, play a substantial role in shaping online conversations about vaccination over the years. These entities exhibit a higher frequency of posting vaccination-related content compared to regular users. Interestingly, the content they share reflects an equal emphasis on both pro- and anti-vaccination perspectives, aligning with a strategy to sow discord on contentious issues—a tactic commonly observed in Russian troll accounts [

87]. One notable example is the Russian Internet Research Agency, founded in 2014 and aimed at influencing on the Internet by disseminating online propaganda, including fake news about the safety of vaccines [

89]. For example, it was demonstrated that while such misinformation tweets rarely contain references to reliable sources, they use anti-vaccination language, refer to various symptoms and personal dangers which are already stressed in headlines, and frame vaccines as a threat to personal liberty [

90,

91].

Today, social media is an important source of information, and there is an even greater need for an appropriate information policy capable of dealing with disinformation. This applies not only to societies as such but also to individual groups, including medical professionals. How else can we explain the over 6% of students who have no opinion about whether HPV vaccines cause infertility, or the 2.2% who have no opinion about vaccines causing autism, and the few people who think this is the case?

A positive conclusion from our study is that the difference between students of younger and older years of study was captured, and older students are less susceptible to the influence of conspiracy theories. This is in line with previous findings [

45,

85,

92,

93], as well as with Baessler et al., who additionally drew attention to the low perceived status of teaching on the topic of vaccinations, especially in the earlier semesters [

94]. However, in the study by Lo Moro et al., as many as 8% of surveyed medical students did not feel adequately informed about vaccination [

95].

It seems that in light of our results, which show a large group of medical students who believe in, or even more often do not strongly reject, conspiracy theories, changes in the content of teaching in this area seem necessary to ensure the proper quality of education. A similar conclusion was drawn by Gautier et al., examining vaccine hesitancy among French healthcare students, who found it to be high [

35]. Similarly to our study, in the case of belief in conspiracy theories, in their case of vaccine hesitancy, a dependence on the year of study was noticed, which should be considered at least a partial success of university teaching. Similar results were obtained in Saudi Arabia by Habib et al., where the difference in vaccine hesitancy for pre-clinical and clinical students was also huge [

92], and by Jamil et al. in Pakistan. It seems that reliable medical knowledge is, to a large extent, an effective tool in the fight against vaccine hesitancy and conspiracy theories [

96].

The crucial role of scientists in disseminating accurate and reliable information was emphasized, along with the potential significance of promoting numeracy and critical thinking skills to mitigate susceptibility to misinformation [

77]. Misinformation surrounding COVID-19 and vaccines, including rumors and conspiracy theories, should not be viewed solely as beliefs in false theories. Rather, they can be interpreted as manifestations of widespread fears and anxieties [

23]. These narratives often arise during periods of heightened social uncertainty, and this is exactly the world we will live in now. Medical students listen to them because they appear in public discourse, and everyone has contact with them, whether they want it or not. The aim of a sensibly conducted health policy should not be to prevent their occurrence, but to deal with them at the scientific level, explaining untruths and simplifications, refuting false myths, as well as providing effective medical education based on scientific facts.

This study is not without limitations. Firstly, although 441 medical students responded and completed the survey, the sample size was still relatively small. Secondly, this research was conducted among medical students at only one Polish university and has a local dimension. For both these reasons, our results represent solely the opinions of those students who completed the questionnaire and cannot be generalized to the entire population of medical students either in Poznan or in Poland. Thirdly, since this study used a quantitative method only, it would be desirable to conduct a more in-depth study using qualitative methods that would help to understand medical students’ opinions on anti-vaccination conspiracy theories. Fourthly, although the questionnaire used for this study was consulted on with two external experts in public health and medical sociology and was pre-tested in a pilot, it was not validated. Fifthly, because this study was designed as an online survey and was conducted via a communication platform used at the PUMS, there is a risk that some students, especially those in their clinical years, failed to receive an invitation.

Despite these limitations, however, the unquestionable strength of this study is that, since there is a scarcity of studies describing the attitudes of medical students towards anti-vax conspiracy theories, it may help to stimulate the discussion on the role of future doctors in enhancing the public’s willingness to vaccinate and overcome vaccine hesitancy. Additionally, by identifying the factors associated with medical students’ beliefs in anti-vax conspiracy theories, this study may also help identify steps that should be undertaken in medical education in order to strengthen their ability to communicate with patients. Finally, carrying out this type of research among students and then presenting them the results obtained could have an educational value and in itself lead to a reduction in the frequency of succumbing to conspiracy theories.